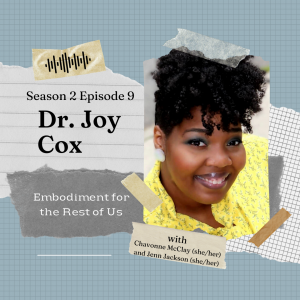

Embodiment for the Rest of Us – Season 2, Episode 9: Dr. Joy Cox

September 8, 2022

Chavonne (she/her) and Jenn (she/her) interviewed Dr. Joy Cox (she/her) about her embodiment journey.

Dr. Joy Cox is a body justice advocate using her skill set in research and leadership to foster social change through the promotion of fat acceptance and diversity and inclusion. With 39 years living as a fat, Black cisgendered woman and 8+ years of professional experience under her belt, Dr. Cox draws on her own experiences and skillset to amplify the voices of those most marginalized in society, bringing attention to matters of intersectionality addressing race, body size, accessibility, and “health.”

Joy has been featured on several podcasts and media productions such as Food Psych with Christy Harrison, Nalgona Positivity Pride with Gloria Lucas, Fat Women of Color with Ivy Felicia, and the New York Times. Her book, Fat Girls in Black Bodies: Creating Communities of Our Own was released in 2020 and has received outstanding reviews and been featured in advocacy work near and far. Dr. Cox is the voice of an overcomer, looking to propel others into a place of freedom designed by their desires.

Website links:

Jabbie – www.getjabbie.com

Twitter – @DrJoyCox

Content Warning: discussion of privilege, discussion of diet culture, discussion of ableism, discussion of healthism

Trigger Warnings:

55:48: Joy discusses legislation that is harmful to the LGBTQIA+ community

The captions for this episode can be found at

https://embodimentfortherestofus.com/season-2/season-2-episode-9-joy-cox/#captions/

A few highlights:

4:10: Joy shares her understanding of embodiment and her own embodiment journey

8:19: Joy discusses how the pandemic affected her embodiment practices

19:10: Joy shares embodiment practices for those adultified as children

33:09: Joy discusses her understanding of “the rest of us” and how she is a part of that, as well as her privileges

44:31: Joy shares the connection between community and embodiment

49:50: Joy discusses how structural change and community impact embodiment

1:02:43: Joy shares how listeners can make a difference based on this conversation as well as where to be found and what’s next for her

Links from this episode:

Music: “Bees and Bumblebees (Abeilles et Bourdons), Op. 562” by Eugène Dédé through the Creative Commons License

Please follow us on social media:

Website: embodimentfortherestofus.com

Twitter: @embodimentus

Instagram: @embodimentfortherestofus

Captions

EFTROU Season 2 Episode 9 is 1 hour, 10 minutes, and 11 seconds long. (1:10:11)

[Music Plays]

[0:11]

Chavonne (C): Hello there! I’m Chavonne McClay (she/her).

Jenn (J): And I’m Jenn Jackson (she/her).

C: This is Season 2 of Embodiment for the Rest of Us. A podcast series exploring topics within the intersections that exist in fat liberation!

J: In this show, we interview professionals and those with lived experience alike to learn how they are affecting radical change and how we can all make this world a safer and more welcoming place for those living in larger bodies and those historically marginalized who should be centered, listened to, and supported.

C: Captions and content warnings are provided in the show notes for each episode, including specific time stamps, so that you can skip triggering content any time that feels supportive to you!

J: This podcast is a representation of our co-host and guest experiences and may not be reflective of yours. These conversations are not medical advice, and are not a substitute for mental health or nutrition support.

C: In addition, the conversations held here are not exhaustive in scope or depth. These topics, these perspectives are not complete and are always in process. These are just highlights! Just like posts on social media or any other podcast, this is just a glimpse.

J: We are always interested in any feedback on this process if something needs to be addressed. You can email us at listener@embodimentfortherestofus.com And now for today’s episode!

J: Hello there listeners and welcome to the 9th episode in our 2nd season of the Embodiment for the Rest of Us podcast. On today’s episode, we have Dr. Joy Cox (she/her) here to ground our conversation on embodiment in her research, connectedness, and her views on an expansive future.

C: Dr. Joy Cox is a body justice advocate using her skill set in research and leadership to foster social change through the promotion of fat acceptance, and diversity and inclusion. With 39 years living as a fat, Black cisgendered woman and 8+ years of professional experience under her belt, Dr. Cox draws on her own experiences and skillset to amplify the voices of those most marginalized in society, bringing attention to matters of intersectionality addressing race, body size, accessibility, and “health.”

J: She has been featured on several podcasts and media productions such as Food Psych with Christy Harrison, Nalgona Positivity Pride with Gloria Lucas, Fat Women of Color with Ivy Felicia, and the New York Times. Her book, Fat Girls in Black Bodies: Creating Communities of Our Own was released in 2020 and has received outstanding reviews and has been featured in advocacy work near and far. Dr. Cox is the voice of an overcomer, looking to propel others into a place of freedom designed by their desires.

C: You can find links to Dr. Cox’s website, the Jabbie app, and social media in this episode’s show notes. Thank you so much for being here, listening, and holding space with us dear listeners! And now for today’s episode!

[3:22]

J: Our second season continues today with Dr. Joy Cox (she/her), who is joining us from New Jersey — someone whose book, Fat Girls in Black Bodies, is one of our absolute favorites from 2020. It really is a must read and we can’t wait to explore it with you listeners! So let’s begin! How are you doing today, Joy?

Joy (X): I’m doing great. How are, how are you?

J: I’m doing wonderful.

C: I’m good. We’re so excited, so honored that you are on our podcast.

J: And fangirling. I have a lot of adrenaline in my body right now, it’s wonderful. [laughs]

C: Same.

[4:10]

C: As we start this conversation about being awake and aware in our bodies, I’d love to start with asking our usual centering question about the themes of our podcast and how they occur to you. So could you share with us what embodiment means to you and what is your embodiment journey even like if you’d like to share?

J: Yeah, so I mean I think embodiment kind of means to me, uhm, being present and, and being your full self and whatever context that is. You know, I don’t think it’s just about being in a place or occupying a place physically but also mentally and emotionally. So just being fully aware and cognizant of where you are and what shoes you’re in and what space you’re in, you know, and and being proud of the space that you’re in and taking up that space fully, owning that space, having agency in that space that’s embodiment to me. Uhm, yeah, so my embodiment journey. I mean, I think that it’s been, umm, more progressive to, to say the least. I, I don’t think that I always started out, umm, fully embodying who I am or or the spaces that I, that I’m in and that I occupy. I think that those things have grown over time. It’s definitely been something that I had to get comfortable with, right? So like comfortable with owning my own space, comfortable with owning my own emotional mental energy capacity, uhm, you know, and all of that. And, umm, and I, you know, and even as a child, I think there were moments where you kind of get a glimpse of what embodiment is, right? To be fully in yourself and be fully aware. Umm, but I also remember there were also times when that kind of got thwarted, right? And so it kind of makes you shrink back, and it makes you question who you are, and if you really deserve to be in the spaces that you’re in. And as someone who’s kind of grown in predominantly white spaces or predominantly thin spaces, you know, deserving to be in this space is something that I think became the norm to be questioned, internally, you know, internally. And so I’m just, just kind of growing out of that and learning I don’t have to question that anymore, or you know I’m not as concerned about people’s comfort with how I embody a space, uh, more how I embody who I am as a person, right? Like, so we’ll, we’ll talk on this podcast and we’ll talk about, you know, fatness and, and using the term fatness, right? And not being as concerned about how people might feel about that or, or those things. Or just, you know, OK, if I’m the, you know, if I, if I’m the, if I’m the fat girl who loves to work out or if I’m the fat girl who doesn’t come fully owning that because I think that there is a lot of criticism that comes both ways with those things. And so my journey has been a mixed bag, definitely. Moments of comfort and peace and then moments of just thrashing and you know and just full out war. And, and that is internally as well as, you know, externally when we start talking about, you know, spaces where taking up space isn’t as welcome.

J: I love just sitting in the word fully, and, and really appreciating that, that there are so many different flavors, variations of embodiment. That, that emphasis on fully just made me feel really grounded and listening to that, I love that, as, as a opportunity, as a goal, even if we can’t do it all the time, even if there’s moments of war. But we can still search for that. I love that.

C: Yeah, yeah. That’s really sitting with me, too, and the idea that it’s not always an easy thing. It’s not always a hard thing. It comes in waves, right? So it’s, it’s a journey. It, it…there’s no destination, it’s just a journey.

J: Mmm.

X: For sure. For sure.

J: I love that.

[8:19]

J: As a human being, how has the pandemic itself affected your embodiment practices in ways that challenge your process? Has there been anything conversely that feels like it connects you further. And what lights you up about your work and when are you feeling most embodied?

X: Yeah, I mean, I think the pandemic has in some ways positively impacted embodiment, right? Especially if you’re somebody who has to work remote, right? It’s like you don’t have to do all the other things that people say make you “presentable” to the public, right? And so I’m more, umm, myself I think during the pandemic and now working remotely full time than I’ve been probably in a long time. And, and so for me, that is something that I really do appreciate is, it’s like being able to connect back with myself in ways where I’m not necessarily having to perform for audiences and be something that I’m not. You know, even if that’s you know, cutting back. So maybe it’s two meetings where I have to show up and look halfway put together as, uhh–[laughs] Right? During an 8 hour day as opposed to you know, really in some ways, 9, maybe nine and a half hour days. Sometimes, you know, showing up where you are, you gotta get dressed, you gotta get washed up. And I’m not saying getting washed up and getting dressed is not a thing, but what I am saying is that there’s a ritual that typically we go through, right, that makes us presentable. And, and being able to, to connect back to myself during the pandemic has been definitely positive. I mean, I think the other parts of that is like with the pandemic, you know, yeah, some things change, right? So in some ways how I move my body changed because I was not going, I mean, I wasn’t going outside and shopping and hitting stores and doing all those things like I was doing before. And so you know routine switched up. And so what does that look like, right? And how are you still at home within yourself? When there’s change that’s kind of happening all around you, umm, you know. It, it, yeah, it’s, it’s interesting to me how you know there was a, there was a push to even still let, like, your identity shine even through mask wearing. Like at some point I was like, you know I can’t just keep doing these regular masks. I’ll do that mask under it, but is there something, something more fashionable? Where’s the colors? Where’s this? Where’s that, right? This place of still wanting to feel, to be you, yourself, to connect back to yourself throughout the pandemic and and in all of those things. And so you know, I think that I went through a lot of similar things that everybody else did and not being able to connect with family regularly. Not being able to see people in person, and, and all of those things. But my alone time and I guess I should flag this and say I’m an introvert. And so my alone time was like really strengthened over. I found myself being strengthened in my long time in ways that I hadn’t been able to do previously, and then everything else I was just in the process of adjusting to do, right? So we change how we move and we change how we kind of function in some ways to accommodate a new normal of sorts. But all in all, I mean, it wasn’t, it wasn’t that bad. I mean, I mean, I think the, the pandemic, you know, really shook up a lot of people’s lives in ways that I will never know, you know. So I didn’t have a lot of family members or anything like that, people who were extremely close to me who passed away solely from Covid. But I think there were, you know, we know that there were a lot of people in this country who experienced that, you know. And for some people, this was the first time their bodies had gotten larger in a long time. And so there was them having to adjust to that, uhm, but you know, I’ve been fat my whole life and so you know you make it, you shift you, make it work, you do what you do. And, and so that wasn’t such a big change for me, but, but ultimately you know kind of being at home with myself was really a moment of, I think, rejuvenation. So much so that when, you know, the call for people to go back to the office, umm, was made, and I was like, yeah, I probably need to look for another job because what I’m doing here is working for me and I like it and I’d like to keep it that way.

C: I’ve heard a lot of introverts really benefited from this because we weren’t…I’m an introvert… were forced to, or not forced but strongly encouraged to interact with other people, I, I definitely enjoyed it for that reason. Umm, I missed touching people.

X: Yeah.

C: That’s probably the only part that I really miss, like, hugging people who didn’t live in my own home, but what really stuck out for me was how easy, how much easier it felt to be yourself when you were at home and you didn’t have to do this kind of performative, uhh, presentation of yourself. I, I heard that from a lot of people that there was a lot of fear for, you know, fat people that I’ve known in my life, myself included, of being perceived again. To go back out into the world when we were able to go kind of back into the world, that, the discomfort of being perceived again, yeah.

X and J: Hmm. Yeah, yeah.

X: Yeah, it’s like a new shell all over.

C: It is, it is.

J: Yes, this is very interesting ’cause I would have called myself an extrovert before the pandemic and I absolutely would not now.

C: [laughs]

J: I have never felt so rejuvenated, so relaxed, so comfortable in my skin and my house. You all can’t see this, who are just listening to this, but like I’m even comfortable with my mess being out for everyone to see. Like in my own office like I don’t…the, the…when talking about presentable was bringing up professionalism for me which includes not just ways in which we’re perceived but also ways in which a lot of people are oppressed in the workplace.

C: Yeah.

J: That they have to do things a particular way, and that’s where their energy has to go, and, and just feeling like the inner introvert of everyone just has gotten a bit of a break. I love, I love that perspective, right? Even if people are primarily extroverted, I think there is something really to be said for having to slow down and having to confront that, especially if you never have before.

X: Right.

J: Like me. [laughs]

C: Same.

X: Right, right, right, right, right.

J: So I really, I really appreciate that, appreciated that.

X: Yeah, and I think slowing down in the, you know, in the pandemic as a whole kind of put perspective on life itself, I think, you know, uhm, you know something in this country is that like we get up and we go. Even if you are in, you know, if you’re in the South or if you’re in another place and things are running a little bit slower overall, as a society, we get up and we go, right? We are working 5, maybe for some people, six and seven days a week. You know, at some point you’re just running on autopilot. You know what you’re gonna wear on Monday. You know what you’re gonna wear on Tuesday. You know what you–where you’re gonna go for lunch. Some of us meal prep, which means we’re probably going to be eating the same thing for four days at a time ’cause that’s how, you know, that’s how you cook it, you know, in bulk, and, and different things like that. And I think the pandemic happened, you know, under horrible circumstances, uhm, but being able to take a step back and saying, hey, has that always been there? Is this how we, you know, have I been doing this thing for so long? You know it’s, you lose sight of sometimes the things that matter the most. It’s like oh I can’t touch my family. I really physically can’t be around the people that I care about the most. And then you start to realize how much that part of your life matters and means to you, right, in comparison to these other things that we tend to put ahead of those things, and I think you know when people talk about the great resignation that happened and people weren’t willing to go back to work. I think some of that was about being able to slow down and really think about what you were putting on the line and what you were getting back in return and for some people they said the cost was too high. And so you know, I think that having time to think, it’s, it’s probably one of our greatest assets in society as a whole. Uhm, but when you think about the more marginalized you are, the less time you have for that, and as a result you wind up making decisions that help you survive to get to the next space, uhm, and that agency gets ripped from you to make bigger decisions down the line, uhm, that could possibly benefit you. And so, no, you’re not thinking about investing, and you’re not thinking about wellness. You know some, some of you, some of us have health insurance, but we’re not going to go see the doctor ’cause we don’t have time, right? Like we don’t have time to do that. We don’t have time to take care of ourselves to do XY and Z, all this other stuff. You know, I’m thinking about survival, survival’s in the forefront of my mind and as a result, the thing that hits me down the road, it’s gonna hurt me more. Uhm, but I’m robbed at that time to really be mindful, to be fully present, to embody a space, atime in my life where it matters. And, and it, and that outcome doesn’t, you know, the outcomes don’t always work out in, in individuals’ favor as a result.

J: Uh, embodiment about what matters. I think that might have been the order of your words, but that’s how they show up in my brain, that, that, that feels really important. We often talk about journal topics when we’re recording podcast episodes and I was just like I want to think about embodiment when it matters. A context feels really important. Thank you for that.

C: Yeah, yeah, I, I agree with you that the pandemic really helped, at least for me, hone in on what matters, who I was willing to give time to, to make sure we could connect however we could connect, because there was so little opportunity for that. Unless you’re doing things on screens and screens are really exhausting. So yeah, I really appreciate that. That’s really helpful.

[19:10]

C: I want to show gratitude for the way you discussed the adultification of Black girls in our society, both in and out of the Black community. It is not discussed nearly enough. How do you suggest those socialized as female seek embodiment when they had to grow up much too fast and may not have as much access to what brought them joy when younger?

X: So I’ll say for me, ’cause I, I experienced adultification, I think, in a different way from, from a very young age, of being in a larger body and I was definitely on the mammy track, if there was a track, right, I was on the mammy track.

C: [laughs]

X: And so I was dressed differently. Things were expected of me differently. I was expected to be the responsible one. People usually don’t know that I am the second of three. Umm, so, I have two sisters, I’m the middle baby. There is an older child, my oldest sister. When people usually meet me, they think I’m the oldest. And I think part of that comes from the conditioning that I had and that I experienced as a child where I was told I had to be responsible for other people. I was expected to carry, uhm, you know, responsibilities in ways that maybe my older sister wasn’t. Uhm, and so you know, uhm, being on that mammy track and, and having things put on you, responsibilities put on you, expectations put on you, clothing put on you. Umm, for me, it was about kind of going back to the roots, kind of going back to the source. When I finished writing the book in 2000, was it, 2019, I think I finished writing the book, well, I was supposed to finish writing the book.

C: [laughs]

X: This was how…I was supposed to have finished writing the book when I took my trip to Dakar. Uhm, and one of the reasons why I took the trip, uhm, I asked myself, what do you want to do? Like if, it was my birthday, I took the trip in honor of my birthday and writing the book, finishing the book, and I asked myself, I said, you know, well, if you’re going to go by yourself, if you’re going to go to a place by yourself, well, what do you wanna do, right? And some of this is like going back to the source ’cause I feel like even though things get snuffed out, sometimes we don’t lose, you know, you don’t lose the roots of the thing that makes you happy. You don’t lose the roots of the things that you’re passionate about, and I think sometimes that’s the beauty of being a human is that people, when they chop things down, they can chop down trees, they can chop down branches, but they typically can’t get to the root right, which, which then gives us hope. If we have the hope, if we have the willingness to rebuild, we let that thing just grow and it’s gonna sprout again. Uhm, and so going back to the roots, I said, well, Joy, what do you wanna do, right? And I like animals and so I was like, you know, I kinda wanna do the whole safari thing. I’m gonna do the safari thing, you know, I like animals, also people always look at me when I’m weird. [laughs] ’cause I, well, they look at me like I’m weird ’cause I’m like, I’m not a beach person, I don’t, I, I mean, after we sit there what we gonna do?

[J and C laugh]

X: Go kick up some sand? Like what we gonna do, right? And so, the, so the beach really doesn’t do it for me. But when people talk about going on vacation, that’s the first thing that comes to mind. Let’s go to the beach. So I’m like, I don’t really want to go to the beach, if you’re going on the trip by yourself, plan something that you want. And so I planned this like you know, the safari thing. I was like, let’s do, you know, let’s find a place that we can go. Uhm, I settled on Dakar in Senegal because I didn’t wanna take a trip, umm, to Africa, I knew I needed the plane ride to work out for me. Nigeria is super long, Ghana, there was the year of return. I was like I didn’t really wanna go to Ghana just to, I didn’t want to go to Ghana to only wind up like in Atlanta, right? So like I go to, I go to see Ghana and everybody from Atlanta is in Ghana, and I’m like, oh, I could have just seen you in the summertime, so I didn’t want to do that. Uhm, and so I settled on Dakar based on the things that I liked. And going back to those places, even if it was by myself, you know, people took pictures of me and stuff and so I get the pictures back and I’m like wow, like I hadn’t seen that smile in years. Like it was like a kid smile, right, like which took me back right, and, and showed me that there were ways that I was connecting back to myself and owning the space that I was in and occupying the space that I was in and having agency and being fully present emotionally and physically in a way that it showed. And…And it’s like beauty. I can’t even, you know…and it wasn’t so much like oh because it’s my face. But you could see genuine happiness, right? Like you could see, like, just genuine satisfaction through the pictures, not because, not because I painted my face, not because I was like doing it for the Gram, not any of those things, right? And I feel like when we talk about adultification, sometimes it’s about going back to the roots of the thing that speaks to you as an individual, right? And I’m not saying that that’s easy, easy, right? I’m not saying that that’s easy at all, because depending on how, what it takes for you to go back to those places, it can be just as painful. But reconnecting back with the roots of who you are and your own identity as a person and then finding ways to stay connected. finding ways to be present in those moments, even if being present in those moments, is something that’s fleeting, right? And so like for me, I was at the safari. I did that thing in Dakar or whatever. I was there for like 11 days, which was probably way too long. [laughs] But I was there and the moments that I was there I really enjoyed myself and I really had a good time. And I had a moment to connect back to little Joy without somebody else saying, Oh well why? Why we don’t just go to the beach or I wanna go to the club? I don’t wanna go to a club, OK? I had–my feet hurt, I don’t wanna go to a club, I wanna go and look at the animals, right? I wanna take pictures. And I was so close to the giraffe and it was just like a moment of like, oh this is, like, when I was seven years old and this is great. You know what I mean? And I feel like those places, moments like that fill me up internally and help me to be whole, right, and help me to move on through different stages of my life, umm, where I’m able to kind of plug holes, right? So that whenever I’m showing up as an adult now, I’m showing up as a whole person and not feeling like I missed out on so much. Like you can’t, yeah, obviously we can’t, you know, we can’t rewind time, right? And, and it’s not to say that you tuck away your trauma and all of those things, definitely heal from that, but some of that healing from that trauma can be to go back to those spaces and reclaim those spaces for yourself. Like I don’t care if people don’t, don’t, no, you didn’t buy a bikini. You know, I don’t care about none of that stuff, like, I like animals. That’s what I wanna do, right? And I think sometimes for Black girls, young Black girls in particular, we get told what we’re supposed to like. We can tell what we’re supposed to do. We get told, and this is, like, in, in culture and outside of culture, we’re constantly being told what we should look like, what we should wear, what we should eat, what music we should listen to. How we should talk, how we should act, what we should shoot for, for the future. And so much that, uhm, some of that can be positive, some of that can be negative, but I think sometimes what we don’t think about is how that washes away what we really want to do right, and so if I really, really, really as a kid, wanted to be a cartoonist, and everybody says that a Black woman should be a nurse, right? Like it may be positive in that people are looking out and they want what’s best for you, right? And they’re pushing you towards that way, and so, no, you don’t get to go outside and play with the other kids. No, you don’t get more time, you know, to, to do the thing that you’re passionate about, but it’s also dimming you, the light. And so it’s always good to kind of reconnect with yourself. And I think for Black women in particular, we don’t ask ourselves enough what do you want?

C: Yes.

X: Right, oftentimes it’s about everybody else, and some of that just comes from the codependency that happens you know, when we talk about, you know, collective cultures. It’s about the whole. It’s about everybody, right? The one person goes to college to and, and that is a, that’s an achievement for everyone. And then you start to think about how you can help your whole family get somewhere better, right? Buy my Mama’s house. I’m buying this person’s car. I’m gonna give this, I’m gonna do, it’s always about somebody else and it’s not until you are, you know, 42, possibly with, you know, kids and everything else that you stop and be like, but what do you want? And now you’re looking around like I got all this stuff and I’m still unfulfilled.

C: Yes.

J: Hmm.

X: And you know what people do? They go back to the root. They said, oh well, I remember when I was 12 years old, when I was ten years old, I had this passion to be a cartoonist, so I started taking classes and now I’m drawing cartoons, right? But you’re 46 now, you know? And so, some of this, long story, right, long explanation is saying.

C: I love it.

X: It’s about going back to the roots and reconnecting with yourself about the things that you enjoy. The things that, you know, that bring you joy, the things that you’re passionate about, you know. And for some of that, some of us that might be childhood like we’ve changed over time, right there it might be in your 20s. I think that if you ask Black women now, when there were times in their life, can they recall times in their life when they felt like their lights were snuffed out? They’d be able to tell you, yeah.

C: Right.

X: So some of that is about going back to those spaces and being able to light a flame, flicker or light, something, right, that helps to, to heal that space and you reclaim those parts of yourself as you move forward.

C: That answer. Whoof! Oh, that was good. I wrote two things down. I could talk for like 20 minutes in response to that, but I wrote a few things down. [laughs] Well, OK, three, because like definitely the minute you said can black women remember the times that lights were snuffed out, my stomach just like…’cause I could just instantly instantly agree with that. That’s just such a painful reckoning. But one thing that I wrote as you’re talking was the body remembers you know this whole idea of this rootedness right, even if we might not have this memory ourselves, our body has these memories of what brought joy like…and like it sounds so funny to just keep saying Joy. That’s just, keeps coming to mind! [laughs] You probably get this all the time.

[All laugh]

C: But the rootedness of it, like your body, I can think of things that make me light up as I do them now, that lit me up when I was five years old and just tapping into that kind of that visible response in your body is what it sounds like you did. And I, I was thinking about that because I love this book. I’m holding it up. I’ve read it a few times. I’ve listened to it a few times. And every time I read it, when I listen to you, and your travels in Dakar like I’m smiling so hard my face hurts and I feel like I can just feel the joy of that, of that trip for you. So it’s just, it’s just a really special, special piece of that book which I already love anyway, but that’s what’s standing out for me right now.

J: Hmm. Fully breathing into your wholeness was, was my way of saying a summary of something you said that like makes something catch in my throat. Uhm, that I was just really sitting with how that’s kept from people, kept from Black women, kept from Black girls, too. But this question of what do I want to do, how do I want to do it, where do I want to go, is such an important life thing for life to be any one person. Uhm, it made me both sad and hopeful. Sad and sitting in that and hopeful about what you’ve said about breathing, about I think you called it relighting the flame, uhh, as a visual for reclamation is really sitting with me. Really beautiful. And thank you, Chavonne, for what you shared. Also, uhm, it didn’t feel long to me, I wanted you to keep going quite honestly.

C: Same. [laughs]

X: Oh. [laughs]

J: It was amazing. Uhm, like truly. Yeah, I loved it, which is also how I felt while reading your book.

[33:09]

J: And actually something was really interesting. In the preface to your book, you refer to ‘what it meant to belong while not really belonging’. Looking at the second half of our podcast name, what does “the rest of us” mean to you? How do you identify within “the rest of us”? We’d also love for you to share your pronouns and name your privileged identities in context here, too. and I know we shared it at the beginning, but in this context here, too, umm, in, in thinking about what it means to belong while not really belonging.

X: Yeah, so my pronouns, are she/her. I, I, if I have privileged identities, I think it is to be able bodied. Uhm, I’m not neurodivergent from what I know. Uh, you, you know, I’m also not a member of the LGBTQIA+ community. Uhm, you know, arguably, I’m not impoverished. Uh, I’ve, I’ve been, you know, I’ve been blessed in some ways to have financial stability in ways that I didn’t experience, that I would say five years ago. But I’m here now and so, and so, I’m grateful for that. I, I mean, those are the identities I think that kind of stick out the most to me. Uhm, I mean, I think when I hear rest of us, I mean, it’s, it’s a, I think, that’s a, a scratchy, it feels sandpapery to me a little bit. Uhm, you know I, I don’t, I, I believe I’m a person that kind of believes that there’s room for all of us. Uh, and so, uhm, and so I do understand, you know, I do understand the…why things become, I guess, fragmented the way that they are and the need for things to be separated or segregated in some ways to benefit marginalized populations as it relates to the things that they’ve missed out on. Uhm, but I very seldom, I mean, I, I don’t think that I actually paid a whole lot of attention to rest of us in that way, uhm? I I read it and I was like OK, Embodiment For The Rest of Us. I get it, I got it. Uhm, you know, uhm, but I think that for me being part of the community that’s often othered, I only talk about being othered when I talk to different groups within the community, there is no rest of us within the community. There is no other. There’s us and and within that space as us, there’s room for everybody. But when I’m outside of that space, then I’m talking to people about how they often don’t make space for the rest of us, right? Or for the people who have been othered but within community. You know we, we talk about there being space for everybody, and then if we have to bring up those terms about rest and other, then we bring up those terms, right? ’cause it’s hard to get, I mean, it’s hard to talk about. Like fatness in and of itself as an identity, uhm, to me really only works if you couple it with something else, right? So you’re a fat woman or you’re a fat man, or you’re, you know, you’re a Black fat woman or a Black fat man or, or you’re a Black fat member of the LG…like, fatness in and of itself doesn’t exist solely by itself. It is attached to other identities that then also create sub narratives about dominant, marginalized identities. So like whenever you’re thinking about it, you know, there’s a narrative about Black women if you become–if you are a fat Black woman, right, that narrative is gonna spin. And it’s going to change a little bit, right, as it relates to your identity within Blackness. Not like oh, this is just a fat creature out here floating like no, the narrative is written about your Blackness as a Black individual, as a Black woman, right? And oftentimes that narrative is going to become more negative than what it was had you just asked a Black woman right now. If you take that same issue and you look at fatness and you attach it to a man whether Black or white, there’s going to be less, this is, there’s less negativity around, uhh, those terms, right? If you are a fat white man, the, the most somebody probably gonna say to you is that you out of shape. But it don’t stop you from getting paid and it don’t stop you from having pretty women on your arm and don’t stop you from making purchases, buying things, etc if you’re a fat Black man, there’s gonna be some negativity that’s associated, but the majority of the oppression that’s going to hit your life comes from the fact that you are a Black man, right? Whereas when we talk about fatness and we couple it, particularly with matters of gender, I can’t get a job, I’m seen as being, you know, I am less educated, I’m making less money, all of those things. And so when we have to bring those, those topics up within the fat community or fat communities that we belong in, that’s when we start to talk about those things. We start to talk about intersectionality and how that impacts the lived experiences of fat people. But if we all know that and if we are all well aware of those functionings, then there’s room for all of us and we can go on and we can have a good time within the community, as a community and we don’t gotta do the whole othering thing ’cause everybody knows where their lane is. And so, yeah, and so that’s kind of how I see that, umm, I’m typically only talking about resting, rest of us, othering, et cetera, et cetera, when it’s people who ain’t part of, who don’t have relationship, really.

J: Oh, oh, so I appreciate that very much.

C: Hmm. It–the way you describe it, and correct me if I’m wrong, it seems like, it feels like fatness is inherently intersectional, like it’s just going to compound on whatever identity already exists. Is that what you mean by that?

X: Right. Right, ’cause fatness in and of itself doesn’t exist without, without those coupling narratives.

J: Uhh, larger context there. Thanks. Thanks for asking that. My brain was just going to ask a similar question to make sure I understood. I, I appreciate that very much. Uhm, zooming out a context, considering things not in a vacuum.

C: I really need to sit with that, but I haven’t heard it that way, like that’s really kind of blowing my mind a little bit here.

J: Me, too. I, I love that. You know, something wonderful about you, Joy, and the way that you express these concepts, that we have both interacted with and talked about a lot, umm, is that there’s always, umm, how I’d phrase this…there’s just places in which I think my privileges keep my brain from continuing forward with a thought. You helped me see what a jump I’m gonna need to make. So that’s why I keep saying I appreciate that. I’m just noticing that I need to jump a little further about this. I need to think about that. I am inside of a vacuum, but these sorts of things are coming up for me. I wanted to clarify that because I don’t want to just say I appreciate without telling you why I’m appreciative.

X: And I think that that’s something though that happens with everybody, right? Like there are things that I don’t think about being able bodied that disabled people think about all the time. So when disabled people say hey this, this, and this, I’m like whoa mind blown just wasn’t there, right? There are, there are things that I’m even, if even that, even if I was the fiercest, like, advocate of disability rights? The fiercest advocate of LGBTQIA+ rights, there are going to be some things that that community experiences and goes through that I will never tap into.

C: Absolutely.

X: I need their stories and this is why whenever we talk about the power of stories. And letting people have voices, this is, this is part of it. This is why we amplify voices, and we don’t say it for other people, because there are going to be things that they are going to be able to tell us that we will never tap into as a Black fat woman. There are things that I’m going to be able to speak to that somebody who’s not Black, fat, and a woman won’t be able to touch. And if we can be OK with that, right? And not sit with because in society we are often taught that there’s, there only can be one, right? So if you’re this one, you gotta be the best at everything. Right? But if you could, if you could sit with that fact and if it makes you uncomfortable, if you can sit with that uncomfortableness long enough for somebody else just to tell their story, you’ll be better for it. We’ll all be better for it.

J: Huh.

C: Absolutely, yes.

X: Right, like me having a different lived experience from you and being able to speak to that is not me trying to step over or do, do more or less or whatever make myself better than like no, I just need the space. I need the space, and you know, and, and if you have the space and you say that you’re for me, give me the space.

J: Mm-hmm.

X: Right, give me the space to be able to talk about it. Give me the space to be able to express my lived experience in the way that I know how to do it, because ultimately it’s gonna make all of us better. And you ain’t gonna be able to, you know, the old folks had a, uh, there was like a saying, uhh, like in church. If you ever went to like, you know, a church that, that’s within Black collectives, right? Like you can’t tell it like I tell it, right, like?

C: Yeah.

X: You can’t, yeah. And, and that’s OK, right? Like be OK, we gotta be OK with that. It’s OK, you can’t tell it like I can tell it. There’s people that gonna tell stuff that I can’t tell the same way and I don’t feel no type of way about that. I’m just gonna slide out the way, let you tell what you want to tell, and then be, fine, and I slide back in when it’s my turn again.

J: Mm-hmm.

X: It’s all right, it’s all right.

J: It is.

[44:31]

C: When I think of you and your work, the word community comes to mind from learning about your travels to your Jabbie App, which creates community in a different way. And also how do you feel finding community helps with one sense of embodiment?

X: Uhm, yeah, so Jabbie is a size inclusive, body affirming, wellness app that I co-founded with Bunmi Alo that encourages people to move their body in their own way. As, as somebody who lived in a larger body who was also active, uh, you know, I wanted to have kind of like a community in your pocket where you can kind of just take it with you wherever you go. Get encouragement when you needed it. Uhm, and then also to, to remove the structure, or the, the requirements around what it meant to be active or fit or all of those things. Uhm, Bunmi’s somebody who, like, really enjoyed working out at the gym and doing all that stuff. And I was like, I’m home, you know, I’m here. Uh, I’m here doing my workouts via YouTube or you know, or different things that I found because that was the thing that helped me be comfortable. And so just kind of being birthed out of that, like, we would, you know, we would talk to each other, text each other, like how did they go? And it’s like I just got done working out and then we would give each other encouragement like oh, that’s what’s up. Like, you know, whatever and through that process that was just something that we were doing. you know, back and forth. One day and I sent the text and I was like what do you think about making this something larger? Like I think it would be great if somebody could, you know, if people were in this space where they could get the encouragement, uhm, you know, and stuff like that. And then like he was on board with that, and so we went around. And I’m not an app developer or any of that stuff, so that was fun. [laughs] I’m trying to figure out who to talk to, and, and all of that jazz. I was just somebody who had a vision, uhm, and was hoping that somebody could bring that to life. And so that’s kind of the basis of Jabbie where people can connect with one another. You know, inclusive trainers also were interested, and so it became a platform where you know, if you wanted to connect with someone who had a background in like inclusive training. That was something that you could do. Uh, and so yeah, so that’s kind of that’s where that’s where Jabbie was like birthed from and continues to be now. Uhm, just as a, as a platform, just something that people can, you know, can share their thoughts, their ideas, also being part of community. Like hey do you know where I can get good shoes to run in? Do you know, you know, what’s good? You know, what’s a good buy if you wanna workout at home? Or, you know, those things. And, and so we just wanted to kind of create a space around that for people to use it. Uhh, and we went live with Jabbie. I think we launched Jabbie in 20…was it 2020? Was it 2020? 2020, I think, maybe it was 2021. Everything is a little bit blurred, I feel like this, like pandemic fog.

[All laugh]

X: Yeah, no, 2020, I think it was 2020, we launched Jabbie. And, and it’s available on Android and Apple. You know, you can, if it’s a tablet, if it’s a phone, all of those things. And I, I mean, I think, I think community can be the cheerleader, umm, to embodiment, right? It’s the thing that, that, uh, that encourages people to keep going, to be themselves, right, to keep living in their truth. And so, uhm, I definitely see community as that support, that, that holds people up and encourages them and gives them legs. When, when theirs are tired, to keep running.

C: Ooh, I love that.

J: Yeah, I love that so much. And you were saying about that, the underlying purpose of this is to change or remove the requirements of what it means to be active. I was just sort of considering being in community about that. To normalize that there isn’t one way to do things, uhm, actually, the only word I have for that right now is wow. And it feels really special and needed and wanted, so I’m feeling really grateful for this space.

X: Yeah, yeah, yeah, for sure. Again, I think, you know, it’s like things that you already know. Uh, but, but we don’t practice them right? We already know there’s not, there’s, there’s more than one way to do a thing right? We already know that, but, but we don’t practice it. Uh, we already know there’s more than one way to be, but we don’t, but we don’t practice it. Uhm, and so I think you know when you are, when we are thinking about the, the realization of Jabbie is that there are many ways to do things, right? And here’s a space where you can feel comfortable in practicing it.

[49:50]

J: Oh, I love that. Umm, and you have to tell me how you feel about this framing, Joy, but that’s actually reminding me of the next question I wanted to ask. And something towards the end of the book that I also can’t stop thinking about, but also feels like…so the word here is going to be structural change, but right now my brain is putting community in there and I’m just kind of sitting with that. There’s a section near the end that says representation is great, but structural change is better. I’m also thinking about the word agency that you used earlier and how just witnessing something or noticing that something is present is very different from having agency and how structures and systems can be in the way of that, and also more specifically, that the first one that we’re having representation doesn’t translate into structural change. There are two different things, so both are really there, and, and needed. So this is often subtext, I hear this as subtext a lot. I love how you’ve already done that. I’m talking about fatness as being inherently intersectional. I love the way you said that, too, Chavonne, that interrelatedness is really something to talk about more on the forward end of things. How do you think representation and structural change can make embodiment more likely or profoundly consistent over time? Or using some other words, you said earlier, more present in our bodies, whether that’s embodiment or not.

X: Well, I think representation and structural change is the golden ticket. I think that’s what people push for and all the times that’s what’s sold to people when they just get representation, right? So this idea that if you see somebody different, that everything else around that person or when that person is involved and it’s going to change. That is the great hope. That is what people are hoping for, right? And so we understand, and I think people who put people in positions of representation understand the power that can happen when representation and structural change takes place. But oftentimes what happens is that people are put in positions to be the representation with no power, and if you don’t have any power, you can’t create structural change. And so, and so to your question, having someone who both has representation and, and the, the, the influence of the power to create structural change, uhm, it absolutely would influence embodiment. It would, it, it, it absolutely would, would change how people see themselves, right? And the agency that they feel within themselves to fully occupy,occupy the spaces of themselves, right? Like there are so many people right now who are lying to themselves about how they feel about themselves, in part because they don’t see representation.

C: Yes.

X: And there, the structure that we have isn’t in place to support the change that they want to be, right? And I think it’d be great to, you know, I think in a, you know, I don’t want to say in a perfect world, but I think that, you know, oftentimes we have this thing where we judge everybody the same way. Like the truth of the matter is that everybody is not going to be trailblazers. Everybody is not going to be fire starters. And those people who have chose to trailblaze and Firestarter, there is something on the inside of them that enables them to do that work against all odds, right, to have the courage to be able to stand up and be like everybody else. This is what I’m gonna do, right? Run with me or get run over. Everybody doesn’t have that mindset, and so there are people who are looking for representation or in some ways, should I say permission to be who they’ve always wanted to be, and that may sound farfetched to some people that may sound like, what, why would somebody wait for permission to be themselves? But they are. Yeah, you know, they absolutely are. To know that, you know, you think about the number of young girls that are waiting for somebody to say it’s OK if you want to work on cars. There’s nothing wrong with you if you want to work on cars. you want to work on cars, it’s OK. Go ahead and work on cars, right? Or the number of young boys, says it’s OK if you like ballet. They do the ballet thing, right? And so, you know, it’s the same thing when we talk about representation and we talk about structural change. There are people who are waiting for the Trail Blazers. They’re waiting for that thing to be birthed, or they’re just waiting for the validation right? That thing, that nudge that says oh, so I’m not, you know, I, I don’t want to be ableist. So I’m not, you know, I’m not losing my mind. I’m not thinking outside, you know, those things. they’re waiting for somebody to say, hey, the way that you are is absolutely fine and you don’t need to change anything up, and so I think that having representation and the power to create new structures or change the structures that you’re in definitely would empower more people, to everybody who that, who they are, right, to occupy those spaces in society and in themselves. And we know it works, and part of the way that we know it works is all the legislation that you see right now happening across the state, right? The Don’t Say Gay thing that’s in, that’s in direct retaliation of the embodiment that people are seeing in individuals in the LGBTQIA+ community. Take, oh, these people are happy to be that, happy to be a part of this community. They’re proud of who they are. What can we do? To change the thing because now representation isn’t enough. No, it’s not enough to have people say that I sit on this board or I stand–I’m the first elected X of this. When you don’t give the first elected X, uhh, this power, right? And yeah, when you start to realize that the people who are embodying who they are, are gonna want everything that’s owed to them, right? Like we’re not cutting no corners. We want everything, right? Then you start seeing these other barriers be put up in place. Same thing with critical race theory. It’s a spin of right wing politics and all of that jazz. But it’s because when, you know, the truth and you connect back to your roots of who you are, where you come from, what’s valuable to you, what it means? You say, oh, wait. You owe me more than what I was gonna ask for before and I would like it all please. Give me all of it since we’re here. I mean, since we already at the table, you know, you invited me to the table, did you not give me all my stuff, right? This is like, oh, ban everything, okay? Right?

J and C: Mm-hmm.

X: Ban anything that has any type of connection to, that’s, that’s the root of the thing. Right? Because the more people know, the more they will feel empowered, the more they feel empowered, the more you want to see them representing who they are. And if you find a trailblazer, if you find a firestarter, if you find somebody that has representation and also power, you’ll birth a nation. Nations.

J: yes.

C: Ooh, I got chills.

J: Yeah, I felt that way at my very core. Right in the core, yeah.

C: That’s really powerful. And it makes complete sense. Everything you said made complete sense. It really, really did. Oh my goodness, Oh my goodness.

J: Yes, Oh my goodness, my brain has gone like 1000 miles an hour.

[All laugh]

C: Oh my goodness, that is spectacular, but I–it, I hadn’t even. I mean, obviously I don’t know what I’m gonna say. I can’t even talk. I’m sorry, go ahead.

J: I also don’t know what to say, seriously, my brain is going so fast. Uhm, that distinction of representation with power like with structural power, uhm? It was just making me sad how very few trailblazers I could think of. Uhm, fire starters and I was just sitting there thinking about some conditioned things in my whiteness that made me a firefighter. Like I put out fires, I have such a strong instinct for that and I was just getting really mad at that.

C: Yeah.

J: There’s real power, real representation is kind of sitting for me. I’m not quite sure about my choice of the word real. But, but it’s tangible, and it’s both.

X: Well, and I think to, to that point, I mean, if you, if you run through your mind and you think about the number of people who both represent marginalized populations and have the means to create structural power, it’s a very small number of individuals. I think your fire starters, your trailblazers, they typically happen without, outside of structural spaces, right? Like oftentimes either they’re pushed out or they know from the onset that there’s no space for them there. And so you know, uh, for some people, compromise is not an issue. That’s not an option, right? And so you probably don’t see them in those spaces as a result.

C: It makes me think as you were talking earlier, I was thinking of all these, you know, these diversity, the DEI, right? Diversity, equity, inclusion boards, hires etc, with no power. And, but they’re like, oh we gotta whatever on the board, we’ve got on whatever in the head of the whatever, and they can’t do anything. So that’s really sitting with me, right now.

X: yes.

C: Structural change has to happen, too.

X: And to that point, I mean the organizations that also hire them, understanding that they are going to block them on everything of risk.

J: Yeah, yes.

X: Right, and so you get sold a good. I mean they sell you on it and they say come on, come and then you wanna do like real rearranging of things and they say no, we can’t do that. No, that’s gonna take a little bit of time. Why don’t you start with conversations, right? So the person that comes in with the fire. Just constantly getting there. Yeah, yeah. Oh, I’m sorry ’cause this is audio. So it’s water, yeah, so they’re constantly right, they’re getting there. They’re getting their fire put out and it’s being reduced to conversations. Just talk about–

C: Let’s have a meeting about the meeting.

X: I had no role change, right? Yeah, right, no role change actually starts to take place or happens. And the person who gets hired for the position is sold under the guise of being able to create change. And oh, we want change and we want it this way and we want it that way. There’s so much bureaucracy across organizations, like you’re never going to get close enough to actually creating change, right? Uhm, but the illusion is there that that’s going to be a thing and so and a lot of lip service.

J: I was just thinking of the statements. I, I mean, there’s been so many statements.

X: Oh yeah.

J: This is who we’ve hired and these are our new visions and, uhm, vision statements and all of that around it, but it’s just lip service, yeah?

X: Yep.

J: That’s what I meant earlier about whiteness and being a firefighter, that water that you were doing was, like it’s like, how can we have someone come in here? Look like we’re doing everything white, right? Well, everything right, also.

C: [laughs]

J: And then how, how can we extinguish this in ways that doesn’t totally put it out so that person is still able to put out these statements? So there’s no real change that makes things right.

C: Right, right.

[1:02:43]

C: We’ve talked a lot about the big and small picture perspectives in this conversation. What do you think we can all do to make a difference with what we’ve learned today? And also what would you like everyone listening to know about what you’re up to and how they can find you?

X: Uhm, you know, I mean, I think that the, the topic or the, the title of the podcast is everything, right? I think what we can do is–anybody, who we are, to walk and live in our troop, and, and and if it’s not to be community for someone, be that support. Be that encouragement so that they can embody who they are. You know, I always talk about this, because when I get asked to do events and different things like that, and people are like, you know, everybody is excited to see me and all of that stuff. And again, I’m an introvert. So I am like the cubbyhole person like, oh that’s nice, thank you. Well, like where’s my dark hole I’m going, that sort of thing, but I didn’t write the book to create more of mes,right?

C: Ooh. Ooh.

X: Like my goal was never to come to make more Joys. Or when I talk, I don’t strive to make more Joys. Uhm, when I talk, what I’ve tried to do is to speak to whatever that thing is and you, that relates to the things that I talk about and hopes that it will ignite whatever magic you have, uh, and then you can run. You can run your own race, right, in your own lane, do your own thing. I can’t speak for everybody else, I only can give you what’s been given to me, and the hope is that whenever I give you what I got that you wanna take it and you’re going to repurpose it in a way that it works for you. That enables you to be powerful and the lane that you have and the race that you gotta run in ’cause I don’t gotta run that race, but once I pass up time to you, I will become the community and I will encourage you and I will support you and I will say run, leap that hurdle, do whatever you gotta do. You know all that stuff. Uhm, and so that’s you know, that would be my encouragement as to like what we can do? Find ways to encourage one another. Find ways to be your full self and, and, and walk in and live the fullness of your own life. Uhm, because I believe that that’s something that, that’s gifted to all of us. We all have the ability to live and walk in the fullness of our own lives and whatever capacity that is, right? Uhm, you know, I, my whole life isn’t dedicated to social justice in the sense that like I’m always here fighting work and moving and pushing like no, those, the, the premise of it I stand by right like when I’m active in it. I’m active in actual work. You know pushing towards it, but then you know I laugh. I don’t, you know, I watch a little Snowfall. I, you know, I, I do those things, uhh, you know, I spend time with my family, I spend time with my friends, because those are the things that help fill me up. Those are the things that help me live life in a very full way for myself. And so that would be my encouragement to everyone else. As far as what Joy is up to., Joy is not up to much. Joy is trying to lay low, Joy is trying to rest a little.

C: Great.

X: We are in the blessed year of 2022 and I think 2022 is when Joy started to feel like the, umm, like the burnout from everything, right? So people like, you know, when the pandemic first started, I have no idea what was happening to me, but I was just like, well, look, I don’t feel a thing. So, you know, I’m running, I’m doing, I’m doing, I’m doing, I’m doing. And umm, and I think this year I actually kind of started to feel a little tired. So I was like, you know, I need to pull back a little bit. You know, I’ve kinda, I had to call some people and be like, oh, I can’t do the project. You know that sort of thing. And so being able to, to still stay connected and talk to people is, it’s definitely what I’m doing. So if you want to say I’m in community, that’s what I’m doing, yeah? Hanging out, you know, hanging out, hanging out with, with everybody else but outside of that I don’t really have anything slated that’s big for me that’s happening right now. And so you, we’ll see, we shall see what the next, you know, what the next moves are, but for right now I’m trying to just rest.

C: And how can people find you?

J: Yeah, so you can find me, I think, probably my website is probably the best way to, to, to stay up, I guess, on what I’m doing. And that’s drjoycox.com, and that’s all one word so DRJOYcox.com. I’m also on Instagram. It’s freshoutthecocoon all one, fresh out the cocoon. I tried to spell that once and it was, like, horrible. So on Facebook, under Fresh Out The Cocoon. But there’s spaces in there, so uhm, so don’t type it in. Then I’m on Twitter as Doctor Joy Cox.

C: Yeah, wonderful.

J: Love your year of rest.

X: Yes oh thanks thanks.

C: Yeah, I, I love that.

X: Or whatever time period it is. Let’s see, I was gonna say, fingers crossed, let’s see if it lasts a whole year, but I need to, I need to, you know, I need to pull back a little bit. So, so hopefully, you know. Hopefully I’ll keep to my word and nothing makes me itch enough that I’m hopping up and doing things and having this same talk with myself in 2023.

C: Doctor Joy Cox, thank, it’s such an honor. Thank you so much. We are so appreciative of all of the knowledge that you have given us and things to think about. It’s been truly an honor. Like I said, I’m such a fangirl. I loved this book. I bought it for like 4 people like as soon as like this and I was like here, here, here.

J: Same.

X: Thanks so much.

C: Thank you.

J: Thank you.

X: I really do appreciate the support and I’m glad that the books spoke to you and have spoken to others. Uh, because ultimately, like I said, that’s the hope so yeah, wonderful.

J: Thank you for all of your thoughtfulness and clarity, I’m taking a lot with me to think about, that is for sure. Awesome, wonderful. So thank you for being you and for being here with us during your 2022 of rest. That makes, I’m, I’m just really sitting in that and feeling really grateful.

X: No, thank you all for having me, I really appreciate it.

J: Thank you until next time.

J: Thank you for listening to season 2 of the Embodiment for the Rest of Us podcast. Episodes will be published every two weeks-ish (because let’s be real here) wherever you listen to podcasts.

C: You can also find the podcast at our website, embodimentfortherestofus.com and follow us on social media, on both Twitter @embodimentus

J: And on Instagram @embodimentfortherestofus We look forward to being with you again next time in conversation.

[Music Plays]

[1:10:11]