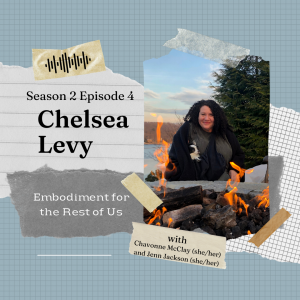

Embodiment for the Rest of Us – Season 2, Episode 4: Chelsea Levy

June 16, 2022

Chavonne (she/her) and Jenn (she/her) interviewed Chelsea Levy (she/her) about her embodiment journey. This is part 1 of our first-ever two-part episode!

Chelsea Levy (she/her) is a Certified Intuitive Eating Counselor and registered dietitian nutritionist. She earned her Master of Science from Hunter College and completed her dietetic internship at the City of New York (CUNY) School of Public Health. Chelsea utilizes Health at Every Size® (HAES®) principles in her approach to nutrition therapy. She works with individuals struggling with disordered eating and eating disorders, with a focus on weight-inclusive medical nutrition therapy, body image healing, and Intuitive Eating. Chelsea has interest in treating individuals with diabetes, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) along with folks, who are in larger-bodies, and those who are transgender or non-binary. She believes it is vital to provide care relevant to an individual’s culture, ethnicity, and overall identities. Chelsea hosts a collaborative space for the exploration of food and body healing through creativity and compassion.

Instagram: @ChelseaLevyNutrition

Content Warning: discussion of privilege, discussion of diet culture, mention of mental health struggles, discussion of dissociation

Trigger Warnings:

58:19: A discussion of fatphobia that can exist when discussing the fatness spectrum

A few highlights:

4:32: Chelsea shares her understanding of embodiment and her own embodiment journey

44:08: Chelsea discusses her understanding of “the rest of us” and how she is a part of that, as well as her privileges

1:33:08: Chelsea shares embodiment practices for folks experiencing various stages of eating disorder recovery

Links from this episode:

Music: “Bees and Bumblebees (Abeilles et Bourdons), Op. 562” by Eugène Dédé through the Creative Commons License

Please follow us on social media:

Twitter: @embodimentus

Instagram: @embodimentfortherestofus

Captions

EFTROU Season 2 Episode 4 is 1 hour, 52 minutes, and 49 seconds long. (1:52:49)

[Music Plays]

[0:11]

Chavonne (C): Hello there! I’m Chavonne McClay (she/her).

Jenn (J): And I’m Jenn Jackson (she/her).

C: This is Season 2 of Embodiment for the Rest of Us. A podcast series exploring topics within the intersections that exist in fat liberation!

J: In this show, we interview professionals and those with lived experience alike to learn how they are affecting radical change and how we can all make this world a safer and more welcoming place for those living in larger bodies and those historically marginalized who should be centered, listened to, and supported.

C: Captions and content warnings are provided in the show notes for each episode, including specific time stamps, so that you can skip triggering content any time that feels supportive to you!

J: This podcast is a representation of our co-host and guest experiences and may not be reflective of yours. These conversations are not medical advice, and are not a substitute for mental health or nutrition support.

C: In addition, the conversations held here are not exhaustive in scope or depth. These topics, these perspectives are not complete and are always in process. These are just highlights! Just like posts on social media or any other podcast, this is just a glimpse.

J: We are always interested in any feedback on this process if something needs to be addressed. You can email us at listener@embodimentfortherestofus.com And now for today’s episode!

J: Welcome to Episode 4 of season 2 of the Embodiment for the Rest of Us podcast. In

today’s episode, we interviewed the spacious and inviting human being, Chelsea Levy. (she/her) about her embodiment journey and nuanced perspective on relational healing and dietetics from a social justice lens.

C: Chelsea is a Certified Intuitive Eating Counselor and registered dietitian nutritionist. She earned her Master of Science from Hunter College and completed her dietetic internship at the City of New York (CUNY) School of Public Health. Chelsea utilizes Health at Every Size® (HAES®) principles in her approach to nutrition therapy. She works with individuals struggling with disordered eating and eating disorders, with a focus on weight-inclusive medical nutrition therapy, body image healing, and Intuitive Eating.

J: Chelsea has interest in treating individuals with diabetes, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) along with folks, who are in larger-bodies, and those who are transgender or non-binary. She believes it is vital to provide care relevant to an individual’s culture, ethnicity, and overall identities. Chelsea hosts a collaborative space for the exploration of food and body healing through creativity and compassion.

C: Thank you so much for being here, listening, and holding space with us dear listeners! And now for today’s episode!

[3:11]

J: This second season is so fun and so exciting and that continues today with Chelsea Levy (she/her) who is joining us from Manhattan in New York City. Someone whose deep compassion and relational perspectives inspire us immensely. There are so many things to explore together in conversation and we’re so glad you’re here listening with us. Let’s begin. So Chelsea, how are you doing today?

Chelsea (L): Hi Jenn, hi, Chavonne!

J and C: Hi! We’re so excited you’re here! [laugh]

L: I’m feeling, I’m so happy to be here. I’m honored to be here, thank you for having me. Well, I’m good, I’m, I will say, like, definitely burning the candle on both ends, but right in this moment I’m feeling nourished like energetically. I’m excited. I’m feeling creative and playful. I’m, I’m hydrated and there’s a fan next to me and yeah.

J: All that just started giving you a picture. I love that and you have a Luna who’s jumping on you and jumping away.

L: Luna, the chihuahua here. She’s making little panting sounds you might hear. So, so yeah.

C: Welcome Luna, welcome Chelsea. [laughs]

L: Thank you.

[4:32]

C: Hi! [laughs] Great. As we start this conversation about being aware and awake in our bodies, I’d love to start with asking a centering question about the themes of our podcast and how they occur to you. Can you share with us what embodiment means to you? And what has your embodiment journey been like if you’d like to share?

L: Yeah, before I get started, umm, I just wanna name that today I’m sort of trying on an experiment of coming into this podcast with no preparation, no perfectionistic ideas, and–just to caveat that there’s nothing wrong with preparation. But uhm, in the act of feeling embodiment, I am trying to be as authentic with my thoughts and feelings to bring it into this interview. So to answer your question on, on the shorthand, embodiment to me means being connected to the physical of the body. And, and I guess more extensively, it’s the levels of connection we have in our subtle energy fields, emotion being one of them, emotion moves in our body through energy. How connected are we to our, the way we relate to ourselves and others, emotionally and energetically. How we feel about gravity in our body, in our state. Uhm, sitting and standing and moving, breathing. What does that feel like? How does that, uhh, relate to our mood and, umm, I guess when I pull back even more, I think about the idea of sort of…if this is just getting a little out there, but if the sun didn’t…I mean if the sun didn’t exist, we wouldn’t exist, but we are operating on gravity on this planet and time based on where we are in relation to the sun and so, so much of what we think about is our constructs. So just thinking about, uhm, standards and and society, as we get into more conversation, it’s just these are all constructs. So coming back to the matter, that is carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, we are all made of the same things and we are all connected and we are not separate and how attuned are we to that connection to me is about embodiment. That’s what, uh, embodiment means to me, uhm, yeah.

C: That’s a really, umm–yeah.

J: Umm, yeah. [laughs]

C: Yes, please. [laughs]

J: I felt that, umm, sorry, Chavonne, go ahead.

C: Oh, it’s okay. I felt that, yeah, in my bones. What I was going to say is it feels very grounding, your explanation. Your definition sounds really grounding, but also sounds really physical. I like that, it’s, I guess that’s grounding, too. I don’t know, but I like that it just feels very…the word coming to mind is concrete, but that’s not what I’m thinking of. I really like it. Grounding, I’m just doing stick with grounding, I really, really enjoy that. Thank you, go ahead. [laughs]

J: I was thinking of the word tangible.

C: Yes! Thank you. OK. [laughs]

J: I, I feel like I can reach out and touch what you were saying.

C: Yes, yes.

L: Yeah, I think that’s what was kind of my goal in, in talking about it. And like that stems from the nerdy science education I have, the experiences of yoga that I have, so that’s like the subtle energy, the science and just sort of like the basic term of embodiment being tangible. I wanted to sort of convey how that is experienced as a human being on this earth, for me and the way I see it based on the constructs that are in place.

J: Ooh and, and you know I, I’ve been trying to like have my brain come up with words for me to say about what it’s feeling like in my embodiment and and listening to you and it felt regulating and what you were describing felt like regulating, like whatever is regulating to each of us is embodying. So I was feeling like oh tapping in. So in trying to unlearn and not be so heavily reliant on my nerdy science side, because I could really get in the weeds there.

L: Yeah. [laughs]

J: I sometimes struggle to keep those things as part of my experience and what I was just realizing, just sort of an own, own tension and tug of my own embodied experience as it changes and kind of evolves with me is that whatever regulates each of us is so valid is something that I was hearing in what you’re saying. Like whichever part of what you said feels valid. There’s, I often call this like the woo moment, right? There’s not like a theory or an equation or anything to point to. It’s a set of sensations of umm, textures, tangibleness, grabbable, was sitting with me. Also like not just tangibles, and I can know what it is like in its shape and what’s happening, but also grabbable. Like I can take that over here with myself and I can try that on. OK. And that felt really important. So I was often, when I think of body image, I think of body imaging like a process. It’s continuous work. Like all these images are happening. I was just sort of sitting in a similar place with embodiment or it’s like, I guess I was realizing that my embodiment can feel very static because I’m keeping the technical nerdy stuff from myself ’cause I’m, I’m trying not to sit so perfectly there. And also there’s so much value there that I find regulating like the why and how of things is very regulating for me. So I was just sort of sitting in that and like oh, I’m fine. So I guess I’m trying to say is, it’s, I’m finding a lot of permission in this to be myself. I’m just describing it in a lot of words, but that’s really what I’m sitting with.

C: Mmm.

L: I love that. Yeah, permission to be embodied. However it is you feel today in this moment because it’s always changing. Energy is always moving. It’s not still or static, even though we can feel stuck or static, we’re always in constant motion or molecules in our body are always moving around. We’re digesting, we’re absorbing, our emotions are changing without always feeling happy or sad, or the nuanced sort of continuum that is, uh, you know emotions. So I love, yeah, that there’s no right or wrong way to embody. Umm, I think about sort of how we participate in society, then create sort of structure that we have to fit into these modes to function. But there is no right or wrong in terms of how we connect or relate to this energetic force that feels, I guess that we experience through our senses in different ways. That’s how I do it.

C: I really love that. Thank you, thank you.

J: Expansive. Permission I’m gonna, I’m gonna add expansive.

C: Very expansive, absolutely. Do you feel comfortable sharing what your own embodiment journey has been like for you so far?

L: Yeah, yeah, definitely. And I guess a couple of the things that I had thought about before I came here was just like, yeah, embodiment the title and just how I, how I related in human, umm. So like just sort of disclosing that I thought, I thought about it a little and, and it’s so multifaceted, but I guess I’ll come, come down to, I feel connected to, uhm, the ground. My body in this, OK that…so there’s, there’s some, these concepts in…I’m in yoga, about doshas and I’m not sure how much you know about doshas? And I’m not a yoga teacher. I just, I’ve practiced a lot of yoga over the years. And so I’ve studied. And I’m, I’m not super active in this moment, but I do sort of like have this toolkit about subtle energy. And so one of the doshas, there’s kapha energy, which is like connected to the earth, and then there’s some…Jenni, do you know about doshas? Just kind of checking in with you on them.

J: I do not, I, I know of them, but could I tell you them, right? No. [laughs]

L: Yeah, yeah. Well there’s air, there’s vata. Uh, uhm anyhow, and there’s pitta, there’s fire, and we all embody all of them. All these energetic sources and, umm…

J: Are they just the earth elements? Am I just realizing that right now? [laughs]

L: They are essentially all of the earth, but like they’re, you know, like earth being, uhh, sort of separate from air and fire, and so I sort of have been identified as kapha pitta. And so that’s like earth and fire. So I’m motivated by my heat and by my, umm, sort of like my belly energy too. And I know this could sound maybe woo for some people out of context, but uhm, I relate to it and sort of if we took it outside of the yogic space, I feel very connected to being still. To sort of come back to that being still being part like comforted, being calm and like kind of low key energy that feels like a really safe place. I am definitely thinking about my childhood and trauma and violence and sort of not to go too deeply in it, into it, personally. But just that food has always been a safe place to bring me back to my earth, to bring me back to my body when I felt unsafe or anxious or scared as a younger person. And, umm, I think in our culture we’re taught that, you know, like emotional eating is this negative thing. But really we have emotions and it’s…we don’t. We can’t really extrapolate that from eating. We are emotional human beings that relate and so all eating is emotional.

C: Right.

L: But what they mean is that, like, like negative eating or eating out to cope with negative emotions is somehow seen as negative in a weight centric model where size is a, is somehow a problem. problematic for us like medically, but also, like in beauty standards. So, so I was always sort of taught like oh like eating for comfort is bad. But actually I’ve learned in my sort of unlearning how it is such a beautiful tool. The problem is maybe when we use it too, and it’s the only tool we have, then it can become problematic. But to have this tool, I feel grateful for. So, my initial embodiment has been, uhm, learning where my safety is and pleasure. And that makes so much sense as a kid, right to seek, to see, search, or as a kid to search for safety.

C: Yeah, mm-hmm.

L: So there’s that. And there’s so many other layers of embodiment of the disconnection and connection, and then where you recognize it, sort of the idea of meditation when we, if we’ve, we’ve ever been in a class or been taught about meditation, like, oh, you have a thought. That’s your, that’s the monkey brain and the monkey thoughts or the limbic side of your brain going. And here, here we go, like pure clouds that float by and we’re going to try to just recognize them and come back to our body. So I relate to that, to that like on and off connection when, when am I feeling disconnected? How do I come back to it? And that relationship is just ongoing I think as a, as a human being. Because sometimes we are overpowered by stimulation and we have to turn off to protect our energy. Sometimes we’re aware of it, sometimes we aren’t, and so learning and unlearning, learning tools to connect to these things more and be attuned and relating to honoring my needs. It’s in, in my body as, as an attunement and sort of a, a way to be feeling really fully embodied, if that makes, makes sense.

C: It makes a lot of sense. [laughs]

J: Yeah, and I’m, I’m feeling like, uh, this feeling of, like, deep breath. Like I want to take a really deep breath. And thinking about what you said about layers, it’s really making me want to get very curious about my own ideas of embodiment that, that sometimes feel like they’re surface level and sometimes feel like they’re deeper and sometimes feel like they’re somewhere in between. But I’m just realizing, I wonder if I’ve had the experience of feeling more than one of those things at one time, or being attuned to them more than one of them at one time, which I thought was just really lovely. And, and, and you’re talking about unlearning that one thing that you can learn is pleasure, which would be one of the biggest bridges to embodiment. I was, and, and talking about the senses, I love that you’re tuning into embodiment as an experience of the senses. Like, really, just like sitting with that. It’s first of all, reminding me of the window of tolerance, but I don’t always like the phrasing of that ’cause why do we have to tolerate anything? And, and also, what I really connecting more with is like a space between over and under stimulated.

L: Yeah.

J: It’s a space between, uhm, feeling very dysregulated in a room like all the way to being feeling very dissociated and disconnected in your body, right? These extremes that exist above this and below this window. And I was just really thinking about how senses anchor us in what you were saying. That’s why it makes me want to explore more like all of the senses at once is totally different from each sense.

L and C: Yeah.

J: Which is also totally different than a situation in which you have some of the senses. I’m just sort of hearing the layers as senses. I think for the first time which is like really resonating. I don’t even know if I have words for that, but it’s like really sitting deeply in my heart right now.

C: It’s…we always come up with journal topics.

J: Yes. [laughs]

C: And I feel like this is my first one. It’s like when I’m feeling embodied, how does it feel in my sense of smell, taste, my sense of you know all of that? Like what does that feel within my body? I really really like that way of looking at it and kind of tuning in that way.

L: I love that actually. Just talking about the, the term window of tolerance, Jenn. When we talk about it, in, in relation to the senses, it feels like it takes away, sort of the, the duality of like good and bad or right or wrong. Or that we should fit into something and tolerate it and more about like permission and curiosity to check in with the wavelength of subtle energy through our senses. Like is it, like what do it, what feels good? What doesn’t feel good? We could change the word tolerance just to a different word and, and connect to all of our senses and feel, feel this embodiment. And the more connected we are, the more aware, self aware we are to connect and relate to others, which is still really empowering. That, that’s what comes to mind.

C: It’s a self witnessing, I, that to me is a real sense of embodiment.

L: That feels empowering in itself.

J: Uhm, it does. And so I’ve got my first journal topic [laughs] as I’m thinking about like if the window of tolerance had another name, what would I name it?? So already I’m thinking of like the window of choice ’cause it’s hard to make choices that honor yourself when you’re over stimulated. It’s hard to make choices or even know that there’s a choice to make when you’re under-stimulated, and just thinking about like what pulls us up or down, right? I, I’m, I’m just using up and down to feel relational, it doesn’t have to be in any direction. Uhm, but just what helps us feel like we’re in there and I’m also just really wanting to consider with myself how often I’m in the window. Like, how often am I actually there?

L: Yeah.

J: Well, uhm, just like thinking about embodiment, a surface level or many layers or super deep. It’s just making me curious. I have no idea what my answer is about myself. I have like, honestly, no idea. But it feels like a great thing to be embodied about checking in is like embodiment itself like a multiple layer kind of embodiment inquiry.

C: Like meta-embodiment? [laughs]

J: Yeah!

L: Yeah, it feels very meta.

[All laugh]

J: Yeah, it’s like I can notice when I feel attuned to my body, like that first level and it’s just making me think especially because embodiment theories often use the word positive, umm, it’s making me curious if it’s making me rebel against even considering my own embodiment in a way. Because when I, when it’s positive, it makes me not want to feel at all. Trauma response! That’s what, what first shows up. I have to work through that every time. Like, oh, am I supposed to be positive about this? What if it sucks? It’s like what my brain starts doing right away. So just thinking like to sit in this space and call it like or even comfort, choice, comfort, something like, what is this state I’m actually trying to be in? Because I’m definitely not trying to be in positive state or in tolerant state or connected.

L: Like you’ve been talking about being really connected and I, I’m, I’m noticing I’m feeling a little spacey just having been vulnerable. And you know just thing like that is, uh, you know, response to my nervous system saying hi, like you know there are shifts happening and just checking in with them without judgment on what’s happening, and they’re, that they’re protective and supportive to us every day and, and as much as I want to connect to this deep embodiment, I think, sometimes, umm, I don’t know like where I’m going with this exactly, but, but sometimes this disconnection is like a, a safe space to be in and, and maybe a level of embodiment that we all need.

J: Oh, that’s, umm…

L: And there’s no shame in that, right? No shame in, in needing space or disconnection. You know it’s about honoring wherever you are because we all have different experiences and we have different needs and where we see the world and feel the world.

C: Yeah, absolutely.

J: OK, I’m not going to go too far into this journal prompts. [laughs] I need to just have a conversation with myself, but, umm, just really tapped into noticing, so embodiment is often talked at, about as looking at what is present. What I was really hearing and, and I’m really getting for myself or just hearing in this situation or conversation is that it’s also noticing what’s absent. That’s what I mean about the word positive. I can only think about what’s present. It’s really hard to think about what’s absent when I’m just thinking from positive perspective and like don’t notice the things that are sticky. I’m, I’m newer to boundaries, admitting I’m angry. I mean like new, whereas in my almost 40 year old life, like literally it’s like two or three years admitting these things regularly to myself, out loud to other people. I’m feeling this kind of sticky pull in my body to not be embodied, to just–I can feel a lot of sensation in my body, which is a really wonderful thing. And also I can feel like an urge to just disconnect completely and, and so right now I feel comfortable just having all this sensation. This is a very safe space in general with both of you, two people I adore so much, also feeling that level of safety. Uhm, recognizing that I’m going to be witnessed about this is, I think the part that makes you want to go, ooh! [laughs] I just like leave my body rapidly.

L and C: Mm-hmm, yeah.

J: And I want to stay here because, uhm, this is something I’ve been trying to cultivate and I’m beginning to realize that what I’m trying to cultivate is embodiment and it’s noticing what isn’t there. When, when I dissociate from my body I can’t notice anything that’s there, so I’m feeling all this sensation, but to kind of–that place of really learning to be with it and like what’s underneath here, what’s missing inside of here. I don’t know. And I really give myself this opportunity so it feels good to just be here in this exploration, and I’m also going to stop myself because I recognize that I’m about to like start doing my journal prompt out loud, which is OK. But it’s just like I, I had this urge to like process it all right now. I’ve written it down. I know I’ll process it.

L: I love that.

J: But it just feels…I have therapy tonight, I’ll do it then. [laughs] It just feels great.

L: That’s beautiful, it’s beautiful.

C: Yeah. Thank you.

J: I wanted to share that, to feel, to be able to feel embodied and no change it. Yeah, listen to it, adding nothing. That’s actually the spot I’m really trying to exist in right now with it.

L: I am, I know we, we might have other other questions but I, I just wanted to sort of add to this. The idea that the word disassociating is not a negative thing. You know, if anyone out there listening is thinking, oh, like I have trauma and I dissociate and like it’s this problem and I need to, you know, get more embodied and connect so I can function, like yes and like no, right? Like yes and no, because uhm, you know it served you for a long time, but, but also like we all have needs to disconnect and there’s nothing wrong with that. And daydreaming or shifting how deeply focused you are is a way to regulate your system. Just like we hydrate and we sweat so that we can be in homeostasis. Our body is doing that through dissociating. And there’s, that’s OK sometimes. I mean I’m not the therapist in the room, but, I, you know, I just feel like it’s important to name as, umm, someone who works with works in eating disorder recovery, there’s a lot of trauma, uh, in the room in, in my clinical work as a dietician. And so, so I want to honor, honor people wherever they are, and there’s nowhere to be or get to other than connect to what you need in that moment.

C: I am a therapist in the room and…

[All laugh]

C: I can absolutely validate and normalize the need for…I was trying to think of a different word other than dissociation, but I’ll say dissociation. It’s a, it’s a safety practice. It’s how I’m going to keep myself safe in this moment, if that’s what you need. I mean, I can see on a personal level, professional level, there are times when I need to remove a part of myself, all of myself, of my brain, of my feelings out of this situation. If that’s what you need to keep yourself safe. That’s OK, absolutely. It’s just…oh now, I’m going down the therapy rabbit hole myself. [laughs] But before…about something becoming harmful, we do things to protect ourselves because they work, right? Like I’ve talked about this many times. I don’t believe there are good and bad coping skills. There are just coping skills that at some point might become more harmful than they are helpful. If dissociating is helpful for you, and it’s something that you can kind of rally from without it becoming harmful for you, great go for it. If that’s what you need to do to be safe, that’s what’s important here.

J: Hmm. Thank you for sharing that.

L: Yeah, it’s a great share.

J: I was thinking of the word adaptive when you were talking about that.

C: Yes.

J: We’ve used this to adapt to stay present physically in a room where we want to leave it mentally. Uhm, when it comes to eating disorder recovery, eating things that feel challenging to give ourselves space to do that, sometimes that also involves dissociation or distraction was also sitting in my mind, understimulation, kind of spaces where we can tune in on a subconscious level and have things feel more regulated while our conscious self just goes offline for a little bit. Just feels really, really important as a step, as a place. And you said, is it helpful or harmful? I was thinking like, I, it feels important to name the system that we’re talking inside at this time like that when it’s patriarchal in nature, when it’s capitalist in nature. The, the signal, the message, the overarching energy and theme all around us is stay on, keep going, get it done.

C: Mm-hmm. Always.

L: Get it done. Be less, do more.

J: So it, yeah, and so to have a chance to be associated or not feels extremely valuable and a little countercurrent that can run within us from all of that shit. I was just sitting, I was naming those words. My brain went shit, shit over there.

L: Can we adapt without it being pathological, you know?

C: Yes, absolutely.

J: Oh oh, I love the way you said it, that gave me chills, right? To not pathologize disassociation and to just let it be something that happened is also a pretty big thing to like let it grieve. It is making me think of how rest is not a dirty word. It’s not a bad four letter word. None of them are really that bad according to me, but there isn’t like the…it’s not something that…you were talking about stillness being your place of reset. Your place of being with yourself, your place of comfort, safety and I was just thinking that rest is so active. As you were describing dissociation is so active, there is a lot going on. It’s just not these ideas that we have to be externally processing and performing and being so visible about it feels like something my rebellious, inner teenagers going let’s rebel against this. This feeling that everything has to be on the outside detectable by another human we can trust ourselves in our process. And to find spaces and have support where we can be who we are in that moment, and whatever processing we need. It feels very rare, very special, very safe, but maybe it’s not rare. Maybe it’s just not as common as I would like. I think it’s more common than we, we may, I may realize in my sort of…I immediately went very dichotomous with that, but there’s just something ’cause healing happens there and healing is so active. Guess what I was sitting with anything else sitting for you, Chavonne, I mean Chelsea. With C named person, Ch person. With this question that she asked, just want to check in.

L: Yeah, I, I see my embodiment as, uhh, always in motion, it’s just, it’s part of being a human being and, umm, there’s continuity to it and I’m adapting all the time and regulating and dysregulating and resetting and I’m noticing it and I’m privileged to be alive seeing it.

J: Thank you for that.

C: I think the only thing I was going to say is I don’t know if I see rest as dissociative. Honestly, I think for me, I can’t speak for everyone. I think it’s a really conscious act for me, maybe because this is the year of rest. I’ve been posting on social media and in my personal life, uhm, that I, I have an intention every year and this year all the signs in the universe told me to rest. I hate it and doing it, whatever. And for me, it’s a really conscious act to rest, like I have to really, it’s silly to say, but put effort into resting, and I think when I think of dissociation, I was thinking about this last just yesterday. I don’t even know why, maybe because we’re interviewing you, Chelsea, and I know you just got engaged, congratulations!

L: Thank you!

J: Yay!

C: And I was like, oh, I was thinking about when I got married. I’ve been married for like 4 years. I don’t know what I’m talking about but like when I had to put on the dress. And like I don’t know why this is coming up, probably ’cause I’ve been decluttering, uhh, but, and I saw the wedding, my wedding dress. [laughs] Umm, and how they had me try it on. And I am, I’m large, I’m a big, I’m fat, I’m a, I’m a larger woman and, but I am not large on top, umm, there’s not much happening here [laughs]. And they tried to put like these like fake cutlets in there. You know and I, like, completely like my mom, like, we got in the car afterwards, my mom was like you weren’t even there and I was like I was not even there. And I like, I like, they were like trying to adjust me and da da da da da and put other things in there and I was like I’m not doing this. But that’s another conversation. And they just kept talking about it, but anyway, I think for dissociation it, at least, the way that I’m thinking about it, I, I’m going to sit with the idea of like rest as dissociation, but for me it’s pulling away. And I feel like rest is moving toward for me, like moving towards something.

L: Ah, I have. So many feelings right now. Just getting excited. I feel like tingly, yeah? This comes back to the doshas and whether or not you know we’re tuned into this higher vedic sort of understanding of energy energy, subtle energy. It’s like we all regulate and dysregulate differently because we have different nervous systems and different dispositions. We all have different personality and energetic flow. And, and so what makes me feel calm doesn’t make the next person problem, doesn’t like, so that’s why rest is maybe more dissociative or less sensitive for someone maybe maybe coming like what feels like a place I can go and escape or not. A really interesting visual, I have a, a, a yoga friend who, uh, was studying nutrition, but uhm, not like a sort of conventional job. She was doing more ayurvedic and functional medicine work. And so we were both on a yoga retreat in Mexico and we were sharing a room and so after dinner we would go back to the room and study for whatever we needed to do. And so I was currently studying protein metabolism, which is pretty intensely challenging. Jenn, you might, I don’t know if you remember those pathways.

J: Oh yeah.

L: They’re not as, they’re not as fun as studying like carb, carbohydrate metabolism. Personally, it just, tt’s like doesn’t feel, it’s like sitting like German or English, there’s like no like rhyme or reason, there’s like, whereas like studying like French or like English or Spanish languages feel like there’s like rules and flow, and that’s how I would really relate it to. So, so, so my like ability, my brain is like going, going, going but my body like really wants to be still, like that, that is sort of like my leaning way of being embodied. OK, so the way that I studied while I was on this trip was laying in bed with like my book like propped up on a pillow while I was like literally like head down on the pillow and like you know, looking up at the book. And my friend studying next to me who feels like much more regulated moving was like standing and pacing and like holding a book in her hand and walking around the room reading her book. And, and like we’re just operating in our own nervous systems and, and that was yeah, just a visual of like how two people can have totally different experiences on regulating.

C: Yeah, that’s a really helpful example. Thank you. To help remind me, but it’s not one…that’s everything, right? Not everything is for everybody like it explains it for me, but it might explain it for Jenn. OK. I really like that, thank you. That was really helpful, absolutely.

J: I love both. I love what both of you said because I was like oh I don’t, yeah, ’cause I think, I actually I’m the one who said rest is dissociation or the same. But I was just sitting with…and I’m like, oh, I could also think of anything that I say, that’s so dichotomous, so black and white, so rigid, I can almost immediately go, OK. I’ve already thought of like 3 exceptions [laughs]to that, so I was kind of sitting in that space. Anyway, I was like you’re reading my mind. I could see rest can be dissociative. I could see dissociation can be restful. I could see how they also feel like they’re really in distinct spaces from each other. Not just person to person but situation is situation for the same person. I was just sort of sitting with, you know, some things that have been mentioned in this little mini part of this conversation. Or like decluttering it’s super active, but there is no peace that comes to me like decluttering does.

C: Right?

J: So active and nothing like engaging and sometimes to get through it, that I love it. I have completely dissociated to stay in my active body part and not try to be in my head like oh, I could keep that, oh, I could do that with this, right? Or my brain will take me in so many directions, I’ll end up in different rooms and not decluttering at all, right? Just like a total tangential, physical experience. So I could even see how in one situation, having the tool of rest like if we were to consider them distinct, even if they overlap sometimes, so can have the tool of rest and the tool of dissociation. I can get things done by using both of those and harnessing them. And so that earlier Chelsea said, oh that’s really empowering. And I just realized today I don’t really think about embodiment as empowering like one word and then the other. Like, even though I can see the potential. But for me, no, that’s not actually what I feel. I have a lot of sensations I have been dissociating from for most of my life. So to be embodied is to be less empowered externally but more empowered internally, and I’m just realizing that even the directionality, I love directionality, but like even the directionality of like what is restful inside, what is restful to engage with other people or a situation outside of me? What is dissociative and therefore I could like check out or not be expending energy or whatever that means in that moment. It’s just very nuanced. This is something I love about you, Chelsea, is everything always turns into this delicious, nuanced, many layered, expansive, almost explosion of feelings and information, but I’m not dissociating. It’s overwhelming, it’s just, it’s just lovely. It’s very engaged, so I continue to feel I’m gonna use the word, extremely. Extremely embodied in this conversation about embodiment. Definitely the most embodied I felt in any of these conversations. But this is who you are.

L: Oh, neat.

J: This is what you pull us into. Uhm, so I love this. I love the nuance. I love even the idea of being wrong right now, I’m like, oh I want to think about that. Another journal topic. I said that’s what I do when I listen to these episodes. I’m like, oh, Jenn, I don’t agree with you. [laughs] I never think that about other people or like I don’t agree with you. I’d say that about myself, I don’t agree with you. And then I think about that. I interrogate that. I get really curious about that, why don’t I agree with myself? But I’m sort of doing it in real time. It’s very interesting. This is also the most expansive answer to this question. Like I’m not saying comparatively, I just mean like the most whatever that I mean to each of us. It’s so lovely like I’m really sitting in the loveliness of this.

L: Yeah, I…like part of me is like, oh, I could just keep going and talking about this and I believe we talked about all these other things and then, and then I’m like hold on.

C: Right?

L: And then I’m like what are they…like those, guys, there’s nowhere to go. Nowhere to get to like you know I’m not, I’m leaning into like perfectly imperfect of, whatever it is, it is. Yeah, it feels very present like everything that’s here is here and everything that isn’t isn’t. And then all of that is fine.

C: Yeah, absolutely.

L: Something just came to mind like in the studies that I’ve done in, in yoga classes and meditation classes. Uhm, there’s often a prompt to lean into the opposite embodiment that you are inclined to do. Like my safe place is to be still but I, I am a depressive person and I need to move. And that actually sometimes is something that’s really helpful for me to regulate and get more embodied in and more connected to what I need. So for other people, it’s really hard to be still, and they’re that, they’re recommended to slow down and be still so they can see and feel connected to themselves, especially with nutrition and eating and nourishing. Like we cannot feel from an empty cup of not knowing what we feel in our body, right? So to be attuned to those connections requires us to slow down. So it really just depends on what we’re going through and who we are, and you know it’s our disposition. But it’s also our, umm, it’s our story of like where we’ve had pain and where, you know, where we’ve been taught, that where there’s pleasure and how we experience it. Yeah, I’m just thinking about that like I know I know where I go when I, when I need, like, to feel, like, safe and that isn’t always what I need to feel involved like to really be embodied. Uhm, but it is my, my automatic reflexive goto, to slow down and be still.

C: It feels really embodied to even acknowledge this is not what I need at this moment, even though this is what I want.

L: Yes.

J: Ooh, need-want. One of my favorite moments, uhh, in places and fine lines of being like, oh need’s here, want’s here, but which one is it?

[44:08]

J: I love this meta, many layered, amazing look at this and it makes me curious about the second half of our podcast title. The rest of us. So I’m curious, what does the rest of us mean to you? How do you identify within the rest of us? And we’d also love for you to share your pronouns and identify your privileged identities in context here, too.

L: So my pronouns are she/her. And my privileges are that I am, umm, able bodied, partnered, educated, umm, employed. I have many. Umm, I am white. And I actually have some feelings and thoughts about that, but I’ll share here which feels vulnerable. And so I’m Jewish, which I see is a marginalization in our world and as a Jewish person, it’s complicated. And I’m not, you know, uhm, trying to find the right way to describe it like totally tuned into it, dialed into it. I’m still sort of exploring what my voice is as a Jewish person that’s not super religious but traditionally identifies and celebrates on a secular level. So like I don’t belong to temple, I go to the High Holidays. Uh, but anyhow, I’m, I’m sort of being tangential. I am–if I left New York City, I would not necessarily feel 100% White, which I know feels probably awkward to say, as like a deeply pale-skinned person in a room that’s not 100%, yeah, privileged in skin color. So I just want to name that I, I am definitely privileged in that my skin is light white and that, uh, I see you know all these as constructs, and so I, I recognize that being Jewish for many people, uhm, who are in light skin just identify as white. But if we are really to get down to it, uhm, the way that I’ve been raised is that like the Aryan race is white that if you are blonde and blue-eyed you are really white, and that if I leave New York City and go out into the, the you know, the country that I, I am in some spaces like more oppressed than not. And I feel safe and cozy in New York City with lots of Jewish people. Umm, so yeah, I am, uhh, you know, vulnerable to say that ’cause it’s sort of a difficult sort of topic, but, but yeah, like it’s there, it’s a marginalization. Umm, being Jewish and like what it comes up with. So to come back to your question about the rest of us and my privileges, yes, many privileges that I stated, and forgive me if I forget any. Umm, when I think about Embodiment for the Rest of Us, I think about who is centered? Who isn’t? And how, how are we treated and how do we identify in that? How do we, how do we, umm, nternalize those, those experiences? And that’s a lot of the work that I do of, of unlearning with my clients and, and myself there. Years of chronic dieting, you know? Lot of unlearning to come back to myself. But yeah, it’s about. It’s about where do you fit or not fit systemically? Uhm, do I fit in chairs? Do I fit on the airplane? Do I fit in clothing and the stores? Am I seen, do I see myself in media or not? And how, umm, how is that identified or celebrated or not, umm, as a fat woman? Who is, trying to think of sort of how to describe this, I’m…I’m never not fat in a room and I don’t, I sort of have mixed feelings about how to break down the like, sort of continuum of fatness. Well, I think there’s an importance of sort of recognizing the level of privilege within marginalization of being fat, like being on the top scale of the infinifat, being the most fat and really not fitting in or seen from the rest of us somewhere that is in the population. Uhm to where I am, which is like I don’t, I can’t buy clothing in the store. I can get it online. I, I mostly fit into chairs, I’m sort of on that cusp of like an MRI machine might be really tight. So it’s scary on a sort of personal level of how the system treats the rest of us. Uhm, that aren’t fitting into spaces in, in the medical model, too, of course, of like medicine being tested and created for, you know, only a certain percentage of people based on a certain weight range. Umm, or like being able to get surgery. Maybe for gender affirming care top surgery based on your size or not. Uh, or I don’t know, any, any particular chronic disease if, if you’re in a larger body having, uhm, the ability to get, uhm, medical treatment that is available because doctors have the right to decline care in most of the states. And so, uhh, I think about that, about where do we all fit in this spectrum of a system that we create in our society to fit in? And, and when we don’t fit, what do we do about that? Whether it’s on an individual level, umm, to take care of ourselves, or on a sort of larger level like for me. As a clinician who has a social justice lens, how do I push the needle to change that? How am I part of the change to fit more marginalizations into that embodiment?

C: You did a really–thank you for that. You, you named most of your privileges as these ones that you were identifying, which I appreciate. How do you identify within the rest of us, like what do you name as your own marginalized identities?

L: So, uh, I am fat, I am a woman, and I’m Jewish. Those would be my 3 marginalizations, yeah.

J: OK. I’m trying to find words for how much I appreciate the nuance that was present in what you said, even things that felt sticky might be the word I would use for that. I’m, like you know, just can feel in my body, the the tension that you were feeling, right? The vulnerability that you were feeling. Uhm, you noted some, the wording that you used was really sticking with me about…you know, previous in season one with Tiana Dodson, we talked about absolute fat and relative fat, like walking into a room and you are fat or not, right? There is in terms of a construct there is that space. You talked about fitting into chairs, fitting into spaces, and I was also sitting on that level and just hearing and realizing perhaps that we talk about it on that level a lot. Like is there going to be a…

L: Fitting in?

J: Like are we literally going to fit into spaces? Are we literally going to fit into clothes, right, ’cause it’s their job. Clothes’ jobs to fit us. Chair’s jobs to fit us. It’s not the other way around, right? So it’s like sitting in that level, but I was also hearing, maybe this is a journal topic, but like in another place. That doesn’t mean that we have affirmed the person, the rest of us. The right to receive weight centric care, but have a chair that fits you is, OK, a pretty big, uhm, separation. It’s a lot to ask of someone, uhm, the surface, and I’m not trying to minimize a chair fitting you because it’s really important to me. And it also, I guess, I’m sort of perceiving this right now as surface level, it’s not. It’s not feeling deep enough for me, all of a sudden, it’s so important, comfort. I’m thinking of airplane seats. Super specifically my own trouble sitting in an airplane seat, especially in newer airplanes where they’ve somehow made them smaller or they weirdly angle them, or you’re like 1/2 seat or these other things. Seat belt extenders and things that quote unquote fit you, but I’m not sure that I’ve, that there’s any increased dignity I might say.

L: Yeah, absolutely.

J: Like why aren’t there airplane seats and that actually fit people? Why isn’t that the norm across the board? We are most of us if we’re talking about people in larger bodies. Why aren’t, why isn’t that? When you’re thinking about marginalization, something I’ve heard you talk about before, Chelsea, is when we center the marginalized, right, it just becomes normal to have a chair that fits everyone. And I do hear what you’re saying, that if someone is outside of people’s perception of fat, right, on the largest end of the spectrum, I wonder if they’d even be included in. I, I don’t know if, if, if chairs accommodate all, every person, for example, I don’t know the answer to that like I’m just realizing some information that I don’t know. But I’m going to guess no. And I was like…

L: I think it can, it’s a hard no. Because yeah, you know, for infinifats, chairs and furniture, if you go to websites for, like, details on products, they have maximum weights and they often don’t fit bodies. My partner and I are fat and we have a mattress that’s for plus size people, but we did a lot of research to find, you know a mattress that supports our body weight because most mattresses don’t think of us or include us in their sales and production.Uhm, this comes back to like legislative and policy work, which isn’t where I personally wanna live or, or be. Like I don’t want to move to DC and work and do this work, but I definitely want to participate and support it. And so I think it’s important to lift our voices of where we’re trying to push that needle against that grain. Uh, uh, you know, for example, creating curriculum like Jenn and I are doing right now that’s weight inclusive for nutrition programs across the country.

J: Yes!

L: In an undergraduate capacity to change the medical models. You know just a, a little taste of, hey, like maybe there’s another way that’s a, a lot more ethical and that’s the beginning of change in a system. Because we’re all individuals that we can’t, we can’t make this shift on our own, and it’s going to take time, but we can participate in that, in that movement, if we, if we choose to in different ways.

C: Yeah.

L: I think about that a lot about, how I’m one human being and I can, what can I do to make a shift in us all being considered just systematically? Systemically, we come first and foremost, but then coming back to sort of like, oh, are we valued and not just seen to fit into, which I think is, is the most important, right? Like in terms of Maslow’s hierarchy, like our basic needs have to be met, but for self actualization to happen for us all. That, that, you know? I’m trying to think of this quote and Jenn, you know the yoga teacher in Texas, who…she’s in a larger body. She talks about, about beauty, that everyone is trying to lose weight to be beautiful, but we are inherently. And I’m like sort of like this isn’t verbatim, but we’re inherent, inherently worthy in , in our bodies as we are already, and that’s not ever considered. Uhm, because it, we’re in a capitalistic society that makes money off of people’s, uhm, not fitting into that centered space right, of, of beauty, ideals.

J: Uhm, yeah, Amber Karnes. Uhm, no, oh no, it’s not. She’s not in Texas. Feels familiar.

L: Yeah, she works a lot with Julie.

J: Shoot, I can’t remember her name.

L: Yeah yeah, it’s OK.

C: I really appreciate your discomfort with the whole idea of the fat spectrum. I think we did–and I have talked about it before and I think we’ll continue to talk about it, but it’s definitely sitting for me. There’s this yet again, more categorization of fat bodies, and I think sometimes it’s necessary. But I also struggle with the fact that it even exists, so I really appreciated that.

L: Well, thank you. Yeah, I try not to over identify with it. It’s like, you know, wherever I am on the spectrum, but I like to identify where my privileges are and my marginalization within the spectrum instead of naming my size. Like, I can fit in a chair versus like I’m a small to medium fat. For example, like I’m naming it, but for the purpose of…it’s not relevant if I take myself and point out like where, where my privileges are as a, in my body in what embodiments are and my marginalizations are. I am very uncomfortable in an airplane seat, but I can fit. I might be like spilling over to somebody else, and it might, it might make them uncomfortable and that is a design flaw on the airplane. Yeah manufacturing, not me. That is, that is, that is a cusp that I’m on and I don’t need to, you know, identify where I am on that spectrum to articulate this, because I think the more that we parse out like this identity, it’s more of of like where we are in the spectrum. I think we can use it and not use it and it just, it’s so nuanced, but I don’t know where I was going with that, but I think it often can be a use of harm. Like, uhm, in that, let’s see on the spectrum, we’re othered. We’re disembodied when we’re othered, in my opinion, uhm, but also like identifying the outliers, like the infinifat, uhm is important, so like both can exist in different ways.

C: Right.

L: Uhm, ’cause these are social constructs so like what is real? What is not real? What’s real are living in a system that doesn’t design things for you. What’s not real is like just the self identity without any context, it’s words, it’s an idea that like sort of loses its meaning like without the identification of the marginalizations or the privileges. It’s just a social construct that loses its meaning.

C: Oh, this is sitting really heavy, uh, only word that’s coming to mind. Uhm, because I, it’s something that I need to kind of sit with personally and repair with other people. Other conversations I’ve had because I definitely have used the spectrum to identify where I am and I yeah, and you’re saying like why? I’m like I don’t, I don’t know, I don’t, I don’t actually know [laughs] So that’s sitting really…it’s making my stomach hurt, right? Like if you’re, if you could see this Zoom video, like I’m scratching my arms as I’m talking ’cause I feel really itchy just thinking about it.

J: Oooh, this, this, the itch that’s like emotional itch.

C: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

L: So I can identify with that because I think…so something important to share that I didn’t share before I realized is that, uhm, I haven’t always been fat. I mentioned that–so my, my relationship to it feels very different than someone who grew up fat and hadn’t had that marginalization as a child, right? That is a different sort of trauma and, and I recognize a privilege of like having been in a straight sized body as a child and not having to experience that. But then to come into being that from weight cycling and chronic dieting and among other things, because there’s like it’s multifaceted. It’s chemistry. It’s biochemistry in the body. We can’t really like parse it out, but always feeling the need to like self-identify like before I stopped chronic dieting but was in a larger body like oh, I’m not really fat. I’m fat because–then I could change that, that idea, even with my education that, that sort of helped me understand that of unlearning. Umm, let’s be clear. I had a very weight centric education in, in dense sciences, in dietetics and a deep unlearning of it as well. And even with my intellectual knowledge, a lack of acceptance that I can’t manipulate my body long term even knowing the statistics because it’s just, it’s a denial piece for sort of like regulating and fitting into our systems of, of not being centered, right? So, so I always felt the need to be, like, well, I’m in a larger body because of this or like, or like you know, like and it’s like, fat bodies are all valid. Whether you were always fat or became fat, like whether you’re fat because you took medication or because you have a chronic illness or because you just genetically are predisposed to it. Like they’re all fucking valid and we need to stop, like explaining why we’re fat. I think there’s this huge need to like self-identify like where we are in the spectrum of fatness and why and I think that is because of thin privilege and medical, medical weight stigma. And I see the relevance of sharing where we fit in that fatness spectrum, some of the time like it just in terms of like being public facing about it, I always question like what is the, what, what am I trying to get across by telling people my size? Am I trying to validate myself in the room? Like that, you need to know I’m marginalized or and which I think is relevant, but there’s other ways to do, other ways to do it. Like, like I can’t fit in this thing or I can’t travel to you because, or like I can’t get this medical care because of my size. You know these are like more specific and like help, sort of, yeah, ground us in understanding each other. Uhm, but in terms of like, I am this size, I don’t know. I’m just, I’m fat and that’s it. And I, I think that maybe if I was an outlier of fatness, this would be a different conversation like I am really never heard or seen like I can’t even buy clothing online, I have to have it made for me, I can’t…I’m like I’m disabled to the point that I can’t, I’m immobile or what you know, like those levels of things. Maybe then it becomes more in the room, umm, but, umm, identifying my privileges and my marginalization around my size help, I think, connect me to my embodiment and to others. And it, it feels weird and icky because we live in this society that’s like really, umm, othering about it, right? Like where there’s a very small percentage of people who are really centered.

C: Yeah, I recently read a book called Don’t Let It Get You Down by Savala Nolan and–which I recommend to everyone, it’s the best. Oh my God, it’s one of the best things I’ve read in years. And she does a really great job. I’ve been talking about celebrating privileges and how icky can feel to do that. But it’s, it’s real life, right? Like we, I’m not saying I’m glorifying, or like lauding myself for being whatever, but I definitely have benefited from privileges, so it’s, right? That’s probably why I feel so icky to even say in my head, like I have celebrated the fact that I’m not whatever. I’m not trying to be fatphobic, but it, it’s, it’s where I don’t know. I don’t, I don’t know I’m itchy. [laughs]

L: If, if, it’s OK, if it’s OK for me to say, umm, I think that’s so human. Uhm, that we feel lucky or gratitude for privileges in a, in a system that is harmful, like it’s, you didn’t do it. You didn’t create this system, you’re in a system and like having compassion for that feels so important. Uhm yeah and I, for the record, like, you know, I’m in and out of naming my, where my body size is. I’m starting to come to a place where I’m like I don’t know how relevant it is, unless it’s maybe like working with a client who needs to hear my story, right, to connect me to heal like publicly, openly without any sort of like containment. I don’t know what to do with it.

J: Ooh, this is so layered and so nuanced, just like we’re talking about embodiment and even the sticky parts of other identities you mentioned, including white and Jewish. I’m sitting with that, too, right now or I’m feeling so icky about that. It’s, umm, first of all I’m feeling very honored to have this kind of conversation because, uhm, it just feels important to explore the nuances of things like both the chance to be, talk about your personal experience. And I’m also hearing that in this space, like each of our personal experiences and also a space to consider the nuances and this one of my favorite things about you, Chelsea. But things can be relational even in that, that stickiness, right? It’s, I also heard the recognition that there are people who are more marginalized that wasn’t lost in what you said. So I think that’s really important and, and like they, they gave me chills and I’m feeling itchy because it’s–

L: Thank you, I appreciate that.

J: So I’m white. I’m in a fat body, but I’m white, white, white. [laughs] I’m pale like you and I always feel like I’m, even in exploring the nuances like just having a conversation, it feels like I’m taking up space that I didn’t mean to take up, but I also think it’s important to explore some sort of I don’t know sitting in both places.

L: Yeah.

J: And also sitting with the like walking into a room as fat. Now that’s not something that I experience. Like I, I’m, I’m not on those margins, right? I did not grow up a child who was fat. I grew…I became fat, so I’m like, I’m just realizing I’m the most privileged person in this room in a lot of ways. Like in the terms of like what other people can be absolute or undeniable or visible, I’m not sure which word is OK. Umm, think I’m going to stick with visible ’cause that feels like really what I’m trying to say that like I can walk into a room and I can be invisible, but not in like in another way. I can just be invisible. Well, that is a possibility for me is something that I’m sitting with here and and sitting with the nuances in this conversation from each of you that there are aspects where you it’s, it is visible. You don’t get to be invisible in that way. I’m just sort of just sort of feeling all of these embodied feelings that I’m feeling and, umm, I just want to sit with it. I just want to listen about that. I just want to like sit in that. The discomfort I feel, but also like the awakening sort of moment. It feels to just sit with that for myself, so I wanted, I wanted to also get vulnerable and share that.

L: Yeah, thank you.

J: And I’m wondering, Chavonne, and I’m not trying to–-I’m wondering if you want to share anything about that or how it feels to have two white women saying this with you. You, you can be like I’m not going to talk about this, let’s take it out.

C: Yeah, I’m not going to talk about this.

J: Okay. Okay.

L: I’m glad you shared that, umm, and I just want to name if we want to take anything out about my feelings about race, that’s totally valid too, and we just hold it in this space about being fat like that’s totally fine. It doesn’t need to be in here. I recognize like full on privilege of being white skinned and like Judaism is complicated and it’s like, really like, really misunderstood in a lot of spaces.

C: Yeah.

L: And I I don’t even fully like, for all intents and purposes, I fill out forms as white and I don’t…I’m not not, I’m not not white but like, I don’t know, I’m just, I’m not Aryan and I’m not…and I…if I go into a lot of places, I’m, I feel othered and disconnected. And I also have a lot of privilege. And I just want to name both and that there’s like something to both of you like I.. I, I don’t see like it’s not, there’s no competition in marginalizations or privileges. We can, we can sit in our privileges and like, be grateful for them, you know. And we can like support each other in our marginalizations to understand what that means for each other. And, and like that and that it all fits.

C: Yeah, I appreciate that I don’t have an answer, I’m just sitting. [laughs]

L: Yeah.

J: Yeah, of course, you don’t have to have an answer. I hope it doesn’t feel like I’m waiting for one.

C: Uhm, before we go forward and I’m probably gonna cut this, I don’t know if I’m going to do it later.

J: You can put anything out you want.

C: I’m sitting with this idea of, Jenn, you saying that you’re the most privileged person in the world, which you are, umm, I’m not denying that. But like I think there’s always this…and because I’m so black and white for lack of a better term. Like, uhm, I’ve always struggled with this like is this me centering myself? ‘Cause I have privilege in different ways. I’m Black but I appreciate, I actually feel quite privileged being dark, like a darker Black, Black person because like there’s never any question of where you were? Like, I’m just Black like nobody questions that.

L and J: Yeah. I mean.

C: That also could be because I grew up in a family that was–there’s a lot of colorism, but kind of reverse, I guess, colorism, that the darker you are, the better you are in my family. Umm, but anyway, uhm, just…I guess I get stuck with this like dynamic of am I centering… like am I speaking up as a way to center myself in this conversation versus am I speaking up as a way to make space for less privileged people to talk? Like I don’t know.I guess that’s kind of where I’m sitting, right? I don’t know. I don’t really have an answer, I’m just kind of sitting with that.

J: Ooh, that’s a very, that’s a good, that’s a…

L: Can you say that one more time? I’m sorry, that last point.

C: Umm, no.

[All laugh]

C: So I guess. I was just like babbling. Umm,kind of this dynamic between am I speaking up because I’m centering myself in this conversation. Or am I speaking up because I am, I’m trying to, I guess have an effort to create more space for less privileged people in the conversation.

J: It’s very important.

L: Oh interesting, that sounds like a lot of emotional labor. I just want to name that.

C: Yeah, thanks.

L: And, and that’s a lot. And I, I just appreciate you saying that, uhm, and being vulnerable, it makes me feel safer when everyone is.

C: Agreed. Yeah, I’m trying not to cry right now, like I feel really, really vulnerable.

J: I, I’m so close to tears. You have no idea. I’m probably gonna cry today.

L: I, I also, I also recognize that like in our–and it’s like whatever we can take this out of the recording ’cause like I do want to center it around embodiment and being fat. But the fact that I shared this piece about being Jewish and like I’m still exploring it for myself of being oppressed but like I still recognize that we live in a country where I have way more privilege and like in the toolkit, like Jenn and I are in like the people we want to pay first are BIPOC and transgender. Like I’m not anywhere like on the top of that list, and I’m, I’m certainly not trying to center my voice. And as an oppressed Jewish person as like historically speaking, I have ton of privilege in my life like as an individual and, and I’m focused on like talking about being fat and like trauma, but like I don’t know. I just like I had family that was like literally killed in the Holocaust, and there’s a lot of feelings about it! So, yeah.

J: Oh yeah, this is so beautiful.

C: I’m not trying to disregard your experience because–there’s a difference between, like…clearly you’re white, clearly. But people are not going to show up at other white people’s places of worship and end their lives because they’re white, like that’s the difference. Like there’s absolutely like, uhh, recorded constant aggression toward your people. That’s–I shouldn’t say your people, that sounds terrible, but you know what I mean.

L: That’s okay. Yeah, totally.

C: So it’s not the same thing to me.

L: It’s not, it, it’s not, it’s really not. You’re right, it’s not, and like I’m not, I’m not gonna put it there ’cause it is…I just guess like just the idea of like being Caucasian is from a specific place. And like I’m Jewish and like so my heritage is like not white even though I’m light skinned and and race is a construct and I don’t identify with it all. But for all intents and purposes I’m fucking white.

C: Right.

L: And like I’m not gonna, I’m not gonna like play around with that. I’m just, I’m playing around with like naming like Judaism, and so I, if this like tossed up any emotional shit or like discomfort, I’m sorry.

C: No, no/ And I also think that that’s what this podcast is about. It’s not just we’re only going to talk about fat people and only that and nothing about anything else than that. That’s–we talk about the margins. We talk about the intersections, not just ethnic or racial, but neurodiverence and you, you know, uh, gender identity, sexual orientation, all of it, all of it, it’s not just that.

L: Yeah, of course, of course, uhm.

J: ’cause it affects all of our embodiments.

C: It does, mm-hmm.

J: Everything that we’re talking about. So I’m just going to say my vote right now. I think all of this should stay in because it’s, it’s fucking perfect.

C: Yeah, and our introduction would be like all right, here it is.

[All laugh]

L: Here’s a, here’s a messy pile, enjoy.

[All laugh]

J: It’s perfect and I want to hear you both say these things and I didn’t even know what you were going to say.

L: I was even planning, I wasn’t even planning on saying that, and like most Jewish people, don’t, don’t, wouldn’t say, identify this way. I, I would say it’s a hard conversation to have and what comes up for, for me is just like people look at my features and they don’t know like what, what are you? And I’m just like, you know, yeah, it’s this other thing.

J: Yeah, it’s like the features version of colorism, I actually don’t have a word for that. But, uhm, where people assume who you are based on what they consider those features to be attached to, as in a, in a socialized way. And I, I something that I’ve really appreciated right now that you’ve said a few times and it’s really been sitting in my head is that these are constructs and right? We’re talking about directionality. We are socialized to see each other as different and some as good and some as bad some in between or ambiguous or whatever the thing is. Uhm, and again, naming the structures that were inside of it upholds patriarchy. It upholds capitalism and all kinds of supremacy, no matter whether that is the social racialized version of supremacy or any other thing that says this is the best, this person, this match. You mentioned Aryan, right? The, the idea that there’s a particular person that is the best just because they have particular features.

L: Let’s be clear, I don’t, I don’t identify that as the beauty standard, the Nazis did. [laughs]

C: Right. [laughs]

J: Right, right. Thank you, exactly, thank you. I, I was just sitting with, wait a minute, I’m not naming, right?

L: I just wanted to name that.

J: But people uphold systems. So why do we bring up this word Nazi so all the way into now, in the future? Because people still identify with that as a, in the power structure.

L: Yeah, our media, our beauty standards.

J: And this, the reason that I’m, I was getting emotional, the reason I’m sitting here, I’m having some release of the embodiment I have been feeling the whole time. Actually it feels really lovely even though it’s sticky and a hard topic is that, uhm, it feels important to, I don’t know, it just felt really important for me to witness that. I actually don’t think I have any other words for that, but it just, yeah, uhm, it felt like an honor to me. You don’t have to say these things in front of me, right? It’s not an. Obligation. You’re not my teachers. And I still felt like I, I feel like I learned and unlearned. Well, unlearning is learning. But I just felt like there was a lot of activity in my unlearning realm in that space and in just witnessing, so it felt really important to me for that reason.

L: Yeah it, it’s, it’s a hard conversation, I think. Like before I was saying–

J: I like hard conversations, live for them.

L: I have marginalization. There’s no competition like we all matter like the rest of us. We all fucking matter. And in our system, in this particular, in this country, but also globally, like there is a hierarchy of like who’s most marginalized and like we need to be real about that. Like even–like, yes, there are constructs and like we, I can talk about that fluidity of like what is real and get meta about it. But like our frameworks that are upheld, that are oppressive like have a hierarchy and like you know I’m not anywhere near the top of that marginalization. And I’m, I’m grateful for it and recognize not fitting in and not being an outlier and like that is, the rest of us. We’re all just in the rest of us, a lot of us, most of us, because that, the centering is a really small percentage of people and it’s, it’s keeping, uh, white men richer.

J: And more powerful and more everywhere.

C: Yeah, I think it’s an important conversation to be had. I’m, I’m thinking about when there was the shooting in El Paso, TX, a year and a half ago. So I grew up there, so that place holds a lot of, a lot of fondness for me. And a friend of mine who I adore, uhm, is Mexican, like she grew up in Mexico. She and like, we went to school in El Paso together. And we had a conversation about it and she, she’s afraid to sometimes acknowledge out loud that you know that the, the, the assault on brown bodies is as much as the assault on black bodies ’cause she feels like she doesn’t have the right to say that. I’m like, but it’s happening, you know? And I think it’s important to give space to that and to where there are no oppression Olympics. I like to make the–I call everything the Olympics. [laughs] Also I like the Olympics but that’s a whole other conversation that I probably shouldn’t like it as much as I do. [laughs] You know, but there are no oppression Olympics, but like you said, there are these, these these systems that encourage the oppression Olympics as well.

L: Yes, yes, that hierarchy exists and we have to, if we are caring about the rest of us, then we need to lift the most marginalized voices and center them.

C: Yeah, yes, absolutely.

J: Hmm. I feel like there’s 1000 journal prompts that could come out of this, maybe a million. [laughs] You know the nature of a podcast is we’re all here talking, so it’s like this strange in between place of like are we centering ourselves but also this is our podcast and we’re having conversation. And I think it’s really important you brought up, Chavonne, about just the question of asking ourselves what is my intention here and also what is my impact, is such an embodied question. The traveling of something from intention to impact is through our body, speaking it, doing it, whatever that is. So I was just really just sitting with not having to have an answer to that question feels actually really important now. I’m just, I’m witnessing, I’m just talking about me, but it just I was like, ah, it’s OK that that question isn’t answered. It’s OK that it felt like do I have any comment here, do I have anything to say? ’cause I feel exactly the same. It’s also was like I don’t want to call you out, but I did it instead of calling like asking myself. So I just want to name that because I’m just sitting with and realizing that that’s what I did. But uhm, I, I think the answer sometimes is just I don’t know as we were talking before or like I don’t know right now, might be the full answer. I’m talking about, umm, dissociation and rest, are there differences and are there similarities? I’m also sitting with, and something that I’m just realizing how important it feels to me and I say this all the time, but it’s like I say it to other people, I think I’m saying it to myself right now. I don’t know, just like the word no is a full response. Letting it just be an idle no actually feels important to be not capitalistic, not fixed, not perfectionist, not anything like that, but to just be in the question. Or even if it’s, I don’t know, just I don’t know empty brain space, which I don’t have, I don’t know what that feels like. [laughs] But like, uhm, not having to arrive at a question that leads to an action, change, or something like that, but to just be with the question is actually something I’m really sitting with in this conversation and mostly listening to the two of you just sitting in that space. I think it’s the space I’m sitting in right now. I don’t know if that makes sense outside my brain.

C: It does.

J: OK.

[All laugh]

J: But that’s, that’s how I would describe what I’m experiencing, which feels like lovely and wonderful in this moment about a hard topic. But I’ve noticed that in our conversation, Chavonne, that we end up, what I end up feeling is like that was lovely. That was amazing. That was hard. Uhm, that was so nuanced, right? That was sticky. I loved it, right? Just a real mix of really strong things like that.

C: Definitely definitely.

L: I know that I’ve said a lot of uncomfortable things. So I’m just naming them. And, and that, like my intention, is so that, yeah, but anyone who feels othered wherever they are, that it’s relevant and they can experience that and identify with it.

J and C: Mm-hmm.

J: We can be related in having been othered without it being identical. That’s what I got from what you just said.

L: Yeah, like I don’t wanna center it above or below any, anyone just, just want it to exist in a space where people know that they are inherently valuable, and if they feel other than that, they’re not alone.

J: OK, I fucking love this, OK?

[All laugh]

C: Yeah, I know I’m just babbling, but I…

J: Go for it.

C: Can I go back to my idea of the Oppression Olympics? So yeah, the Olympics are so fucked in so many ways. I should stop saying that. [laughs] So fucked in so many ways, like even think about how the Olympics are…

J: The Oppression Championships, we’ll come up with something.

L: I like that a lot.

C: Yeah, we call it the Suffering Olympics in our marriage. Like you don’t get to win the Suffering Olympics today. It’s so terrible.

[All laugh]

C: Yay,, couples counseling. but I…

L: Yay!

C: Yeah, yeah, I, I, I guess I’m struggling because again, like you said, Jenn, you can say something and 5 minutes later it’s like I don’t like what I just said. And that’s where I am right now, so. There is no…there’s a hierarchy and there’s not a hierarchy is, I guess, just what I wanted to say. And that’s not saying that we must be like, oh, but this is how I suffered, da da da da da. But there has to be some acknowledgement that like there is a hierarchy of oppression.

L: Yeah, there is.

C: To be a queer, I’m sorry to be a trans Black woman is to be the most targeted person in this–marginalized, most targeted, most marginalized person in this country.

L: Yeah.

J: Thanks. I appreciate that.